EVALUATE UPSTREAM:

OPTIMIZING THE HOMELESSNESS PREVENTION ASSISTANCE SYSTEM IN CHARLOTTE-MECKLENBURG

Appreciative Inquiry Explained

Appreciative Inquiry (AI) is a philosophy of change management that is strengths-based and grounded in positive psychology. One of AI’s key underlying principles is that what we choose to study makes a difference; if we choose to focus on what’s broken, our orientation will be problem-centered. Alternatively, if we choose to study and build on strengths and what is working or has worked in the past, we will support and do more of it.

Process Design

The project was designed to occur in five phases. Phase I focused on a homelessness prevention resource inventory mapping and research into national and global best practices in prevention practices. This phase also included a retrospective study of the experiences and housing outcomes for callers to a helpline who were seeking housing assistance over a six-month period.

Phase II was dedicated to an Appreciative Inquiry process of capturing the positive stories of residents of Mecklenburg County who had firsthand experience with housing instability or homelessness but managed to avert homelessness through various means. We were interested in learning about sources of strength, resilience, support and resources that contributed to success in stabilizing their housing situations so that, going forward, those success factors could be replicated and scaled. The findings from Phases I and II provided the foundation for the subsequent phase of work in which a Design Thinking process was undertaken to reimagine a more effective prevention network.

From the outset, the success of the AI process was predicated on recruiting community members as prospective appreciative interviewers who brought grassroots credibility and authentic voices. This was necessary to overcome significant lack of trust in community-wide change initiatives that have historically been top-down. Participant recruitment for the first AI Summit focused on people with lived experience with housing instability, frontline workers within the public sector and nonprofit agencies providing housing-related and critical needs services, community and housing advocates, and representatives from the private sector with a history of volunteerism and advocacy in the housing and homelessness space. A total of 30 interviewers were recruited for participation in the AI Summits and subsequent interviewing process, of whom 25 attended one or both summits. A total of 21 appreciative interviews were completed.

The Appreciative Inquiry Summits were held virtually due to the COVID-19 pandemic from August through October of 2020. The four summit sessions were convened on Zoom for the whole-group sessions and to provide the privacy of breakout rooms for paired interviews and small group discussions. The facilitators used MURAL, a shared virtual whiteboard technology, to develop themes and emerging priorities in real-time with the whole group.

Participants were divided into two cohorts for AI Summit I, which was hosted in two identical half-day sessions. Summit I introduced participants to the philosophy and practice of Appreciative Inquiry and provided an opportunity to engage in paired appreciative interviews with a prepared script. After the preliminary round of paired interviews, the pairs were merged into groups of four, and then reconvened as a whole group to share commonalities across their interview responses. Finally, the participants returned to their breakout rooms to craft interview questions for their upcoming interviews with community members who were previously unstably housed. The whole group was reconvened one final time to prioritize and select questions to be included in the final interview script. Each participant was assigned to conduct one appreciative interview with a community member who has overcome homelessness or housing instability.

Four weeks after Summit I, a second AI Story Sharing Summit was held – once again, with two cohorts assigned to two identical half-day sessions – to hear the personal stories of how community members prevailed over housing instability.

Working first in small groups and then as a whole group, the AI interviewers recorded common themes on worksheets and in MURAL, deliberated the Positive Core and prioritized interviewees’ recommendations for the Design Thinking team to incorporate into their design process. In parting, the summit participants were invited to indicate their interest in continuing their participation in the Design Thinking phase of work with an expanded team of participants. Ultimately, 12 individuals from the AI phase volunteered to continue on into the Design Thinking phase.

Positive Change Results

The process of changing Charlotte-Mecklenburg’s approach to preventing homelessness is still in the very early stage. The process of compiling learnings from all phases of work is ongoing.

The design of this process, which focused on positive stories of success and inverted the usual top-down, hierarchical approach to planning the way forward, was well received. The AI Summit participants were reassured that the process would be more inclusive and grassroots, which, in turn, led them to “vouch” for the credibility of the process with somewhat reluctant interviewees.

The quality and authenticity of the stories that were captured enriched the planning process; the voices of those who have successfully overcome homelessness and housing instability will substantiate those components of the current prevention system that should be retained and expanded, as well as those that should be abandoned. AI interviewers were moved and inspired by the stories that they heard, which deepened the commitment among some of them to continue participating through the Design Thinking phase of the process.

Insights and Lessons Learned

There were several challenges associated with undertaking a big system reform project using Appreciative Inquiry during a pandemic. A virtual summit cannot replace or replicate the interpersonal connections and energy that occur during an in-person summit. Additionally, a virtual summit only accentuates any disparities in access to technology and high-speed internet that exist between well-resourced and under-resourced participants.

Institutional sponsorship (or the lack thereof) is very consequential in a big system, community-wide change initiative. In this instance, the success of pulling together a disparate group of loosely affiliated or unaffiliated stakeholders who did not have accountability to a “higher authority” was dependent upon pre-existing relationships or relationship formation and the participants’ innate sense of commitment to the issue of homelessness prevention. This did not always result in follow-through on summit attendance or completion of interviews.

In planning for the recruitment of interviewees, we underestimated the reluctance that we would encounter among folks who have been at-risk for homelessness – even those who have successfully overcome housing challenges. Initially, the trained AI interviewers were asked to interview individuals with whom they had an established relationship – either as friends, neighbors, peers or former service providers. However, due to the stigmatization of unstably housed individuals, even when it is caused by circumstances beyond their control, there lingers a sense of shame and humiliation about having to relive the story through its telling. Ultimately, we relied upon nonprofit and public sector service providers to assist in recruiting, through whom we were able to recruit 21 additional interviewees. Gift cards were sent to interviewees as a token of appreciation upon the completion of interviews.

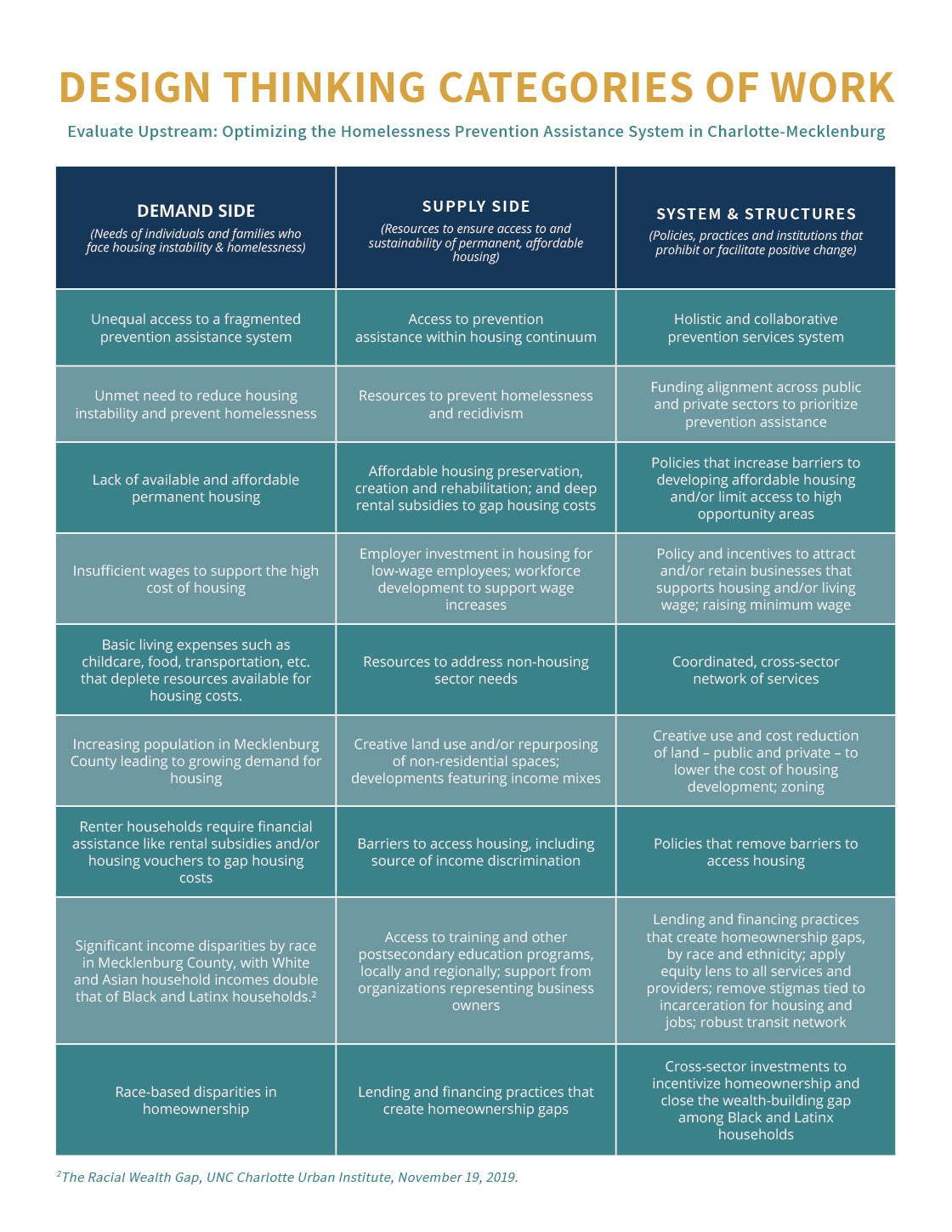

Design Thinking Categories of Work

“Homelessness prevention refers to policies, practices, and interventions that reduce the likelihood that someone will experience homelessness. It also means providing anyone who has been homeless with the necessary resources and supports to stabilize their housing, enhance integration and social inclusion, and ultimately reduce the risk of the recurrence of homelessness.” ¹

Connecting the Dots Across the Data

It is helpful to have a framework within which to understand the interdependence of factors that contribute to and perpetuate homelessness. To understand the context for this work, we reviewed data from multiple reports including the 2020 Charlotte-Mecklenburg State of Housing Instability & Homelessness Report, Evaluate Upstream: NC 2-1-1 Study, recommendations from the Appreciative Inquiry Summit on homelessness prevention, prevention assistance best practice research and The Racial Wealth Gap – Charlotte-Mecklenburg (November 2019). We determined that the related themes and strategies that follow could be categorized by demand side factors, supply side factors, and systems and structures that contribute to homelessness.

Demand-Driven Factors

Demand-driven factors pertain to essential needs of individuals and families who are at risk of homelessness. These include unequal access to prevention assistance services, lack of available and affordable permanent housing, insufficient wages to support the high cost of housing and income disparities by race and ethnicity.

Design Thinking challenge: Using a racial equity lens, through what short-term and long-term strategies might we address the gap between wages and housing costs for cost-burdened, low-income households in Charlotte-Mecklenburg?

Theme 1: Largest Problem Remains the Gap Between Wages & Housing Costs

- The majority of people experiencing housing instability are employed or have some source of income.

- Wages among the lowest income categories are not keeping up with the rate of increase in rental housing costs. In fact, wages are effectively decreasing because they are not keeping up with the rate of increase in the cost of living in Charlotte-Mecklenburg.

- According to the Evaluate Upstream: NC 2-1-1 study, the most frequently cited causes of housing instability were the lack of available affordable housing (35%), lost jobs (24%) and insufficient income to afford housing (6%).

Theme 2: Housing Cost Burden Is Increasing, Resulting in Increased Housing Instability

- 44% (or 81,611) of Mecklenburg County renter households were cost-burdened in 2018; 20% (or 36,735) of renter households were severely cost-burdened.

- The percentage of renter households who are cost-burdened (paying more than 30% of income on housing-related expenses) has increased 22% since 2010.

- Among callers to NC 2-1-1- seeking housing assistance who found resources helpful, direct financial assistance for rent/hotel/motel was most frequently cited, followed by a 2-1-1 referral for housing.

Theme 3: Racial Disparities Exist Among Households Experiencing Housing Instability

- Black and Latinx employees are overrepresented in jobs in the lowest income quintile and overrepresented among callers to NC 2-1-1.

Supply-Driven Factors

Supply-driven factors center on the creation and/or preservation of resources to ensure access to and sustainability of permanent, affordable housing. They include access to prevention assistance within the housing continuum; resident displacement prevention; resources to prevent homelessness and recidivism; affordable housing preservation, creation and rehabilitation; deep rental subsidies to close the gap in housing costs; employer investment in housing for low-wage employees; and workforce development to support wage increases.

Design Thinking challenge: Through what cost-effective strategies might we promote access to and increase the inventory of affordable housing, including new development, preservation of existing affordable housing, repurposing of underutilized non-residential structures and availability of deep rental subsidies to gap costs for market rate units?

Theme 1: Access to and Availability to Permanent Affordable Housing Is Decreasing

- The inventory of affordable rental units at or below $800/month has decreased by 26% between 2010 and 2018, falling from approximately 51% of the total rental stock to only 25% of the total stock. Median rent in Charlotte-Mecklenburg is now $1,063 for a 2-bedroom apartment, which requires a monthly income of at least $3,600 ($43,200 annually).

- From 2018 to 2020, the number of rapid re-housing (RRH) units decreased 16% (46 units) and the number of permanent supportive housing (PSH) units decreased 5% (57 units). This decrease is due to both a decrease in financial assistance (such as rental subsidies) and number of physical units.

- The local Housing Trust Fund has supported the development, preservation or rehabilitation of 10,369 total units between FY2002 and FY2020. After deducting the total number of units that were emergency shelter beds for people experiencing homelessness (694) and the total number of units that are pending and/or under construction (3,599), this equates to a total of 6,076 total new units over 18 years or 338 new units on average per year. These 6,076 units also rent in a range from 0% to 80% AMI and even includes some market rate units.

- Households with housing assistance face additional barriers, like Source of Income Discrimination (SOID), to access available permanent, affordable housing. 44% of rental applications placed by Housing Choice Voucher holders between April and December 2019 were denied. In addition, 7% (or 53 households) who were experiencing homelessness and surveyed on the night of the Point-in-Time Count had some form of housing subsidy in hand but were still unable to access permanent, affordable housing.

Theme 2: Supply-Driven Solutions Must Go Beyond Construction of New Housing Units

- Recommendations from the Appreciative Inquiry Summit included finding creative ways to increase new and preserve existing inventory of permanent, affordable housing in different types of neighborhoods throughout Charlotte-Mecklenburg.

Systems-and-Structures-Driven Factors

Systems and structures include the policies, institutions, systemic practices and funding, and the organization of resources that can aid or impede homelessness prevention. In coalescing around prevention, systems and structures must fuse legislative, policy and funding frameworks across sectors.

Design Thinking challenge: How might we forge a measurably effective cohesive, coordinated, and holistic multi-sector network of prevention assistance that will keep individuals and families from entering homelessness?

Theme 1: There Is No Coordinated, Prevention Assistance System

- A network of services that is explicitly focused on homelessness prevention does not exist in Charlotte-Mecklenburg.

- The current network of resources is fragmented — with limited access points, and coordination across providers — and not designed to optimally serve households at risk of homelessness in a holistic way.

- The resources to which at-risk callers to NC 2-1-1 are referred are not coordinated and are not viewed as helpful by callers (as reported by 66% of those surveyed in the NC 2-1-1 study).

- Households at risk of homelessness are largely unaware of resources that are available to assist them from a prevention standpoint, and they do not know how to navigate the system or how to advocate for themselves.

- Effective prevention efforts require a person-centered system of services that is decentralized to neighborhoods, is empathetic in approach, preserves dignity and sense of humanity, and engages community-led organizations and people with lived experiences to serve as housing navigators.

Theme 2: Resources to Which At-Risk Households Are Referred Are Not Demonstrably Effective

- Among callers to NC 2-1-1 for housing assistance between January and July 2020 who were not referred to Coordinated Entry, 58% said that their housing issues were not resolved; 24% reported that their needs were temporarily resolved; 17% reported that their needs were permanently resolved.

- Among callers who were referred to resources by NC 2-1-1, 66% reported that the resources were not helpful while 34% reported that the resources were helpful.

- Of sampled callers to NC 2-1-1 who were not referred to Coordinated Entry, 53.4% reported that they were living in hotels/motels, 20.6% were residing with friends or family members, 15.3% were lease-holding renters and 7% had become homeless.

Theme 3: An Effective Homelessness Prevention Network Requires a Multi-Sector Redesign of the Current Array of Services

- The redesign process should engage individuals who have been impacted or are currently being impacted by homelessness and/or housing crisis in the Design Thinking process.

- An effective prevention network must improve awareness and availability of housing-related resources.

- A cross-sector approach to homelessness prevention is essential and must be designed with shared accountability.

1 Stephen Gaetz and Erin Dej, A New Direction: A Framework for Homelessness Prevention, Canadian Observatory on Homelessness, 2017.