Courtney LaCaria

Housing & Homelessness Research Coordinator

Mecklenburg County Community Support Services

In October, Mecklenburg County Community Support Services released the 2021 Charlotte-Mecklenburg State of Housing Instability & Homelessness (SoHIH) report. The report provides a single, dedicated compilation of all the latest local, regional, and national data on housing instability and homelessness pertaining to Charlotte-Mecklenburg.

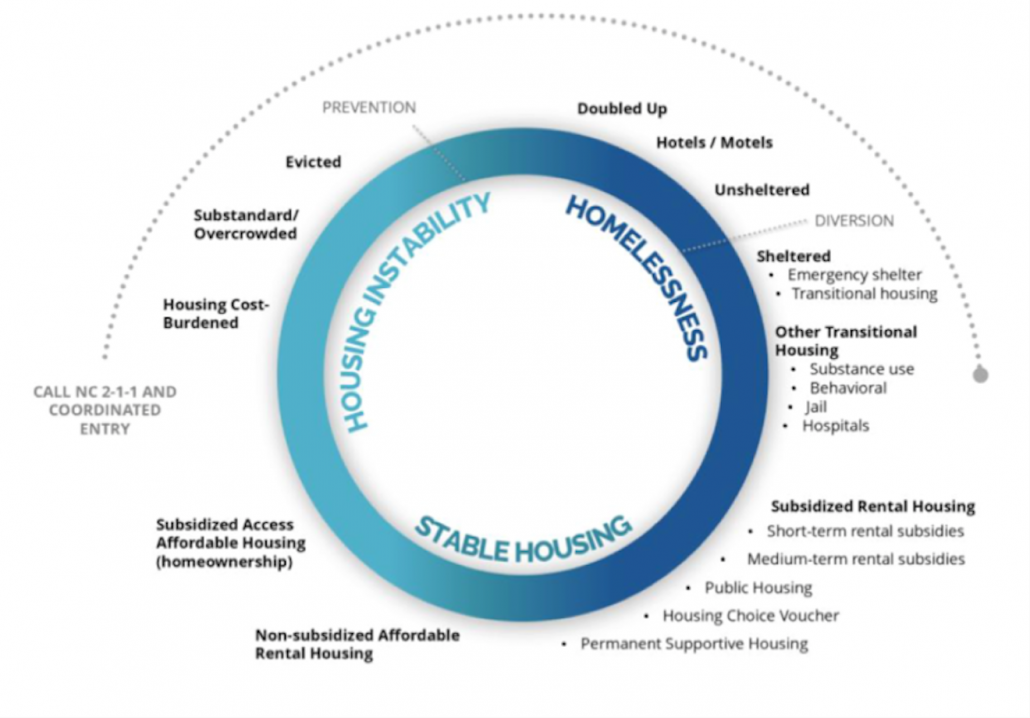

The report is intended to be the “go-to” resource for all stakeholders working to address housing instability and homelessness in Charlotte-Mecklenburg. It is anchored by the three main components of the housing continuum: housing instability; homelessness; and permanent, affordable (or stable) housing. As the report is designed to make information easily accessible, there are also complementary materials available; these will help connect the data with stakeholders. These resources include the Key Findings Handouts, Report Toolkit, and Housing Data Factsheet.

The blog post from October 14 shared three key themes from the 2021 SoHIH report; and blog posts from October 21 and November 4 unpacked the first and second themes. This blog post will take a deeper dive into part of the third theme, regarding how the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed housing problems that were hidden prior to the pandemic; and ultimately, what this means for Charlotte-Mecklenburg.

A NEW (?) FORM OF HOMELESSNESS, OUT OF THE SHADOWS

After the North Carolina Stay at Home Order was issued in 2020, the NC 2-1-1 system was flooded with calls by households seeking housing and financial assistance. NC 2-1-1 is the number that households who are facing a housing crisis in the state call to be connected to resources. In fact, during the first two months of the pandemic, the number of households seeking rental assistance in Charlotte-Mecklenburg increased by 900%.

In addition to an overall increase in the number of callers, a “new” population experiencing homelessness began to present: households paying to stay in hotels or motels. While this type of homelessness existed well before the pandemic, it had been considered “hidden”. Because of the need to protect both individual and public health, communities like Charlotte-Mecklenburg, had to ensure this newly recognized population had a safe space to stay at home, and then to isolate and quarantine if needed.

Homelessness is a type of housing status that exists along the housing instability & homelessness continuum. This continuum, including the different types of homelessness, is visualized in the graphic below.

Homelessness, by definition, means the loss of housing. Homelessness occurs when a household lacks a fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence. This means things like doubling up with family and/or friends; paying to stay week to week in hotels/motels; temporarily residing in a shelter and/or transitional housing facility; experiencing unsheltered homelessness; exiting an institutional setting within a determined period of time after previously experiencing homelessness; and/or fleeing domestic violence.

The definition of homelessness employed varies by funding source. There are some definitions of homelessness, like paying to stay week to week in hotels, which had little to no federal, state and/or local resources dedicated to addressing it, pre-pandemic. This type of homelessness is also not included within the annual Point-in-Time Count because it is not part of the definition set by the U.S. Department of Housing & Urban Development (HUD). It is, however, included within the definition of student homelessness under the McKinney-Vento assistance program, but there are limitations: the number of students experiencing homelessness is an annually reported cumulative number; it does not include all the members of the student’s family; and it only includes those students who get connected to McKinney-Vento resources.

Households who are experiencing homelessness and paying to stay in hotels and motels do, in fact, have income. In fact, the amount paid for daily, weekly, or monthly “stays” in a hotel is often higher than what a household might pay in rent or mortgage for a comparable space. Despite having income, barriers such as high security deposits; poor credit ratings; eviction histories; and debt conspire to keep some households stuck in hotels and motels and excluding them from accessing permanent, affordable units.

While this type of homelessness predates the pandemic, COVID-19 has exacerbated conditions for households struggling to pay the daily, weekly, or monthly rates in hotels and motels. Households have faced underemployment and unemployment resulting from the economic shutdowns; they have also had to reduce or eliminate necessary expenses like food, healthcare, and transportation. As an early response to COVID-19, Charlotte-Mecklenburg allocated funding for and enacted protections to ensure that over 1,000 of these households could safely “stay in place.”

SO, WHAT

In 2016, groups from the public and private sectors formed the Community Response to Homelessness in Early Childhood Alliance (CRHEC) in Tarrant County, Texas. CRHEC has the goal of addressing early childhood homelessness in the county. The members of CRHEC knew early on that the available estimates were undercounts because the definitions for homelessness failed to include everyone. According to the county’s Point-in-Time Count data (which uses the literal definition of homelessness that includes emergency shelter, transitional housing, “safe haven,” and unsheltered homelessness), there are on average 300 children reported to experience homelessness on any given night. In 2019, school districts in Tarrant and Parker counties served 4,908 school aged children during the academic year; of that total, (86% or 4,221 children) experienced homelessness in doubled-up situations or in hotels or motels. However, at the end of their process, the CHREC Alliance found that there were actually 14,981 children under the age of 18 experiencing homelessness each year in Tarrant County.

During the last decade, Charlotte-Mecklenburg has improved data collection and reporting on housing instability and homelessness. The launch of the The One Number in 2019 represented a significant step toward a more comprehensive, timely enumeration of all the people experiencing homelessness in Charlotte-Mecklenburg. However, there are still many households who experience homelessness (as well as housing instability) who are not captured as part of the One Number. Getting the number right is important: we need to know and understand how many people are experiencing all forms of homelessness to effectively define the scope of the problem to inform funding and policy decisions.

An important outcome of the work of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Housing and Homelessness Strategy (CMHHS) is alignment, to present a more comprehensive picture of the full housing continuum. This work includes identifying and closing gaps in data collection and reporting, as well as developing more inclusive definitions to encompass all the aspects of homelessness and housing instability.

Stay tuned for future blog posts, which will take a deeper dive into the other key findings from the 2021 SoHIH report. There will be no Building Bridges blog post next week, as Mecklenburg County is closed in observance of Thanksgiving.

On Thursday, November 18, 2021 at 7:00 PM, the Homeless Services Network (HSN) will host the annual homeless vigil, remembering those who were homeless and who died during the past year. Please click this link to access the virtual event.

SIGN UP FOR BUILDING BRIDGES BLOG

Courtney LaCaria coordinates posts on the Building Bridges Blog. Courtney is the Housing & Homelessness Research Coordinator for Mecklenburg County Community Support Services. Courtney’s job is to connect data on housing instability, homelessness and affordable housing with stakeholders in the community so that they can use it to drive policy-making, funding allocation and programmatic change.