New Report on Homelessness and What It Means for Charlotte-Mecklenburg

A new report called The 2017 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress released this week by the U.S. Department of Housing & Urban Development (HUD) provides national and statewide numbers on the number of people experiencing homelessness on one night in January 2017.

This blog post will break down information in the new report, compare the new information to local Point-in-Time Count numbers, and offer three takeaways for Charlotte-Mecklenburg.

What is the report?

The AHAR is the first part of two reports that are submitted annually to Congress by HUD to inform funding and policy decisions. It provides national data from the 2017 Point-in-Time Count and includes estimates of people experiencing homelessness, and the number of beds to temporarily and permanently house people experiencing homelessness as part of the Housing Inventory Count. The estimates of people and beds are reported by 399 Continuums of Care (CoC) across the United States.

The 2017 AHAR Report includes a baseline number for unaccompanied youth homelessness. An unaccompanied youth is defined as an individual under the age of 25 experiencing homelessness on their own and not part of a household. The report also provides the first examination of changes in demographic characteristics of people experiencing homelessness.

What are the key findings and how does it compare to Charlotte-Mecklenburg?

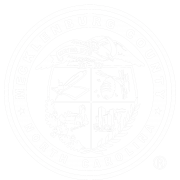

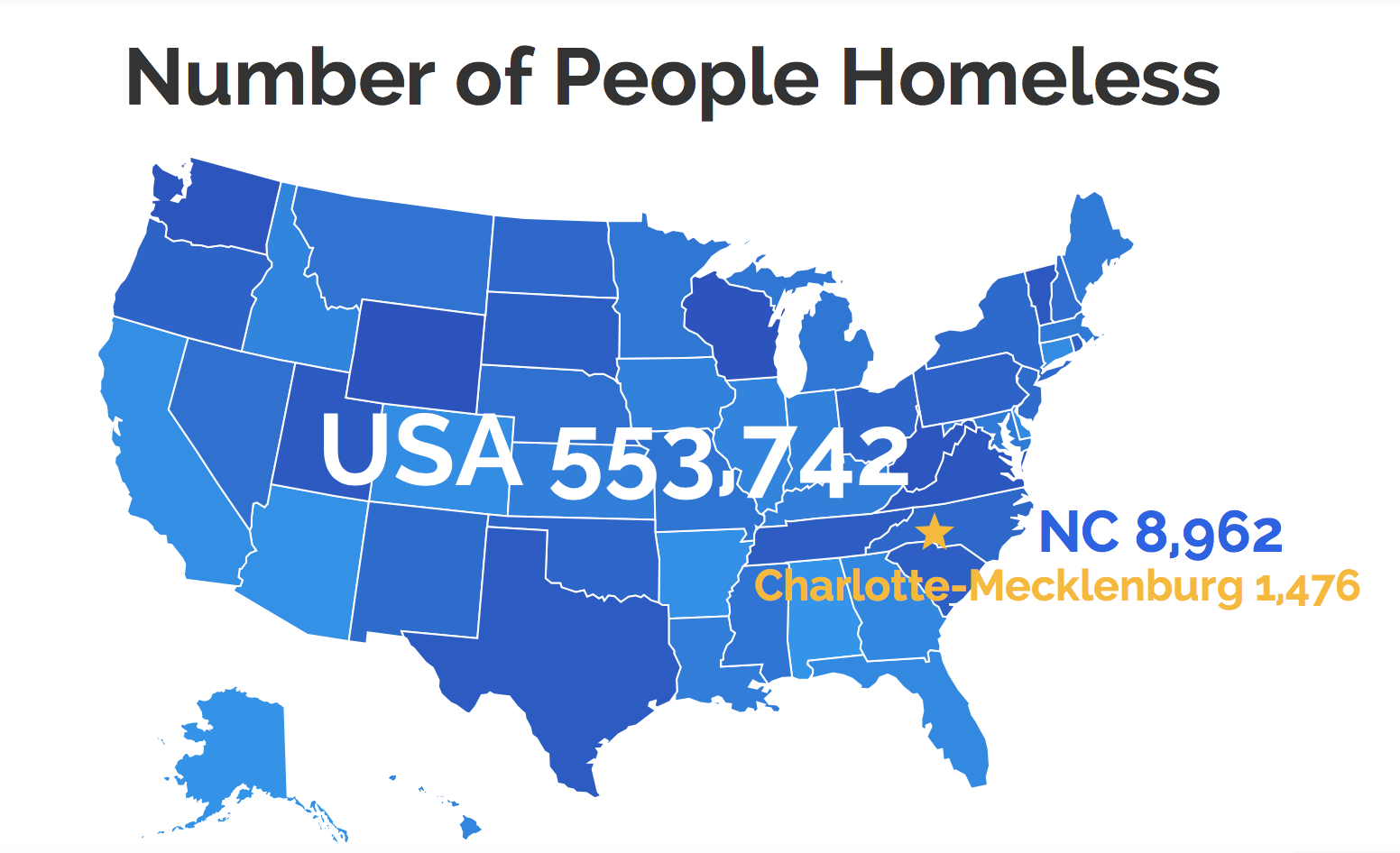

The total number of people experiencing homelessness on one night in 2017 was 553,742 people, which represents an increase of almost 1% (3,814 people) between 2016 and 2017. It is the first time homelessness has increased in the last seven years. Since 2010, homelessness has decreased 13% (83,000 people). Most people – 65% (360,867 people) were staying in emergency shelters or transitional housing programs and 35% (192,875 people) were in unsheltered locations.

North Carolina experienced a 6.2% decrease in homelessness between 2016 and 2017 and a 26.5% decrease since 2010. Compared to national numbers, a smaller share experienced unsheltered homelessness with 27.3% (2,451) total people.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg decreased overall homelessness 12% between 2016 and 2017 and 26% since 2010. Compared to higher national and state numbers, 15% (215) of the total population of people experiencing homelessness were in unsheltered locations.

What accounts for the change?

Most of the national increase in 2017 is driven by an increase in unsheltered homelessness, which increased 9% (16,518 people). The unsheltered homelessness increase is driven primarily by increases among individuals in the 50 largest cities in the United States, especially along the west coast where there are significant challenges with the rental market. The report shows that if that data is removed from some of the high cost / low vacancy rental markets where increases were reported, the national total would show a 3% reduction in total homelessness, 7% reduction in family homelessness, 6% reduction in veteran homelessness and 4% reduction in chronic homelessness.

North Carolina and Charlotte-Mecklenburg also experienced increases in unsheltered homelessness even though the overall population of homelessness decreased. Between 2016 and 2017, North Carolina’s unsheltered population increased 6% (142 people) and Charlotte-Mecklenburg’s population increased 15% (28 people). The increase in unsheltered homelessness statewide and locally has become a trend in the past few years.

Regional Variations

Some communities across the United States experienced increases and others decreases in their numbers of people experiencing homelessness. A small number of communities had a large impact on the national totals. 60% of Continuum of Cares (237 CoCs) reported that they had reduced total homelessness and 40% (162 CoCs) reported increases.

There are 12 CoCs in North Carolina. Including Charlotte-Mecklenburg, seven of the CoCs experienced decreases in homelessness and one experienced no change. The largest percent decreases were in Gastonia/Cleveland & Gaston, Lincoln Counties CoC (24%), Greensboro/High Point CoC (21%), and Wilmington, Brunswick, New Hanover, Pender Counties CoC (17%).

A closer look at population categories

2017 AHAR: Part 1 – PIT Estimates of Homelessness in the U.S.

Families with children

The number of families with children experiencing homelessness in the U.S. decreased 5% (3,294 households) between 2016 and 2017 and 27% from 2010 to 2017.

The only age group within families experiencing unsheltered homelessness that increased was among people between the ages of 18 and 24 in unsheltered locations (an increase of 317 people or 26%).

Nationally, between 2016 and 2017, homelessness among people in families who identified as African American increased 3% while declining among people in families who identified as white (10%).

In Charlotte-Mecklenburg, the number of families with children experiencing homelessness decreased 35% (78 households) between 2016 and 2017, which was mostly due to a decrease in the population in transitional housing.

Veterans

The number of homeless veterans in the United States increased 1.5% (585 people) between 2016 and 2017, which represents the first time veteran homelessness has increased since 2010. This increase is likely due to the 18% (2,299 people) increase among unsheltered veterans. Since 2010, veteran homelessness has decreased 46% (34,000 people).

Compared to other types of homelessness, North Carolina has a lower share of veteran homelessness with 931 total veterans, comprising 1% to 2.9% of the total population of veterans across the United States.

When looking at the CoC level among smaller City, County and Regional CoCs, the Asheville/Buncombe County CoC has the fourth largest total of veterans with 239 people. There were 137 veterans in Charlotte-Mecklenburg, which experienced an 8% decrease between 2016 and 2017. The number of unsheltered veterans in Charlotte-Mecklenburg stayed relatively the same (25 in 2016 and 24 in 2017).

Chronic Homelessness

The number of people experiencing chronic homelessness nationally increased 12% (9,476 people) between 2016 and 2017, but decreased 18% (19,100 people) between 2010 and 2017. Increases were seen within sheltered populations and unsheltered populations, and were steepest in major cities.

Compared to other types of homelessness, North Carolina has a lower share of chronic homelessness with 994 total people, comprising 1% to 2.9% of the total population of people experiencing chronic homelessness across the United States.

There were 147 people experiencing chronic homelessness in Charlotte-Mecklenburg, which decreased 14% between 2016 and 2017. Almost half (47% or 69 people) of the total people experiencing chronic homelessness were unsheltered.

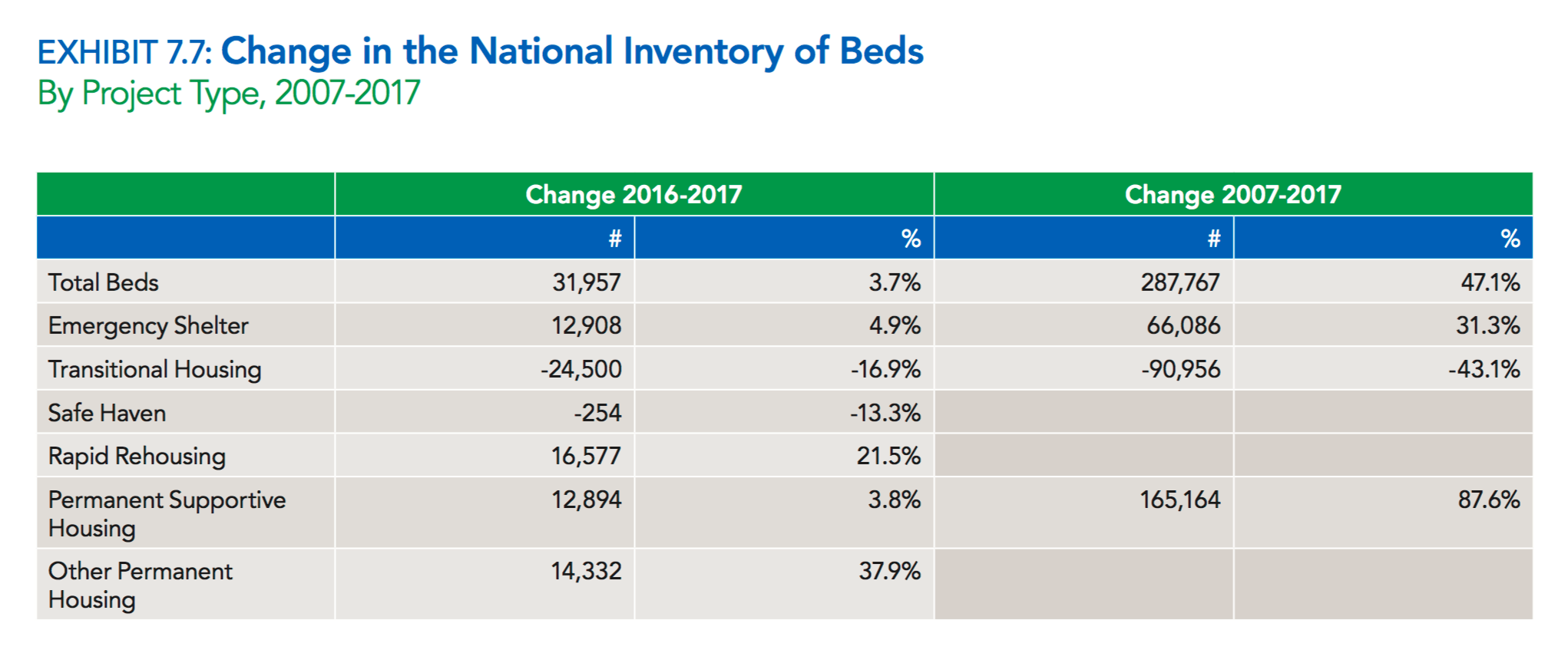

In 2017, there were nearly 94,000 more permanent supportive housing (PSH) beds dedicated to people experiencing chronic homelessness in the United States. Although permanent supportive housing beds can be dedicated to people experiencing homelessness, only 42% of all PSH beds in the country are dedicated to chronic homelessness. Charlotte-Mecklenburg dedicates 100% of its PSH beds to people experiencing chronic homelessness, which is in alignment with national guidelines. Since 2010, PSH beds in Charlotte-Mecklenburg increased 270% (938 beds).

Youth

There were an estimated 40,799 unaccompanied youth under the age of 25 experiencing homelessness in the United States on the night of the Point-in-Time Count in 2017. Most unaccompanied youth (88%) were between the ages of 18 and 24 and were more likely to be unsheltered (55%) than all people experiencing homelessness (35%) and individuals experiencing homelessness (48%).

Transgender youth accounted for 2% of the unaccompanied homeless youth population. People who did not identify as male, female or transgender comprised a very small share of the overall unaccompanied homeless youth population but were much more likely to be unsheltered than sheltered.

There were 66 unaccompanied youth in Charlotte-Mecklenburg on the night of the Point-in-Time Count with 27% (18 people) in unsheltered locations.

Demographic Characteristics

Nationally, 47% or 260,979 of all people experiencing homelessness identified their race as white. 41% or 224,937 people identified as African American. In Charlotte-Mecklenburg, 79% (1,170 people) of the total population experiencing homelessness identified as Black compared to 31% of the general population in Mecklenburg County that identifies as Black.

Between 2016 and 2017, overall homelessness among people identifying as Hispanic or Latino decreased 2% (1,880 people) across the country. Unsheltered homelessness within this group increased 30% (10,261 people). In Charlotte-Mecklenburg, 4% (60 people) of the total population experiencing homelessness identified as Hispanic or Latino compared to 13% of the general population in Mecklenburg County that identifies as Hispanic or Latino.

Beds

2017 AHAR: Part 1 – PIT Estimates of Homelessness in the U.S.

There were 899,059 total beds available on a year-round basis in emergency shelters, safe havens, transitional housing, rapid re-housing, permanent supportive housing and other permanent housing. More beds (56%) were dedicated to permanent housing than temporary places to stay (44%) like emergency shelter and transitional housing.

In Charlotte-Mecklenburg, there were 3,984 total beds available in 2017 and 65% (2,595 beds) were dedicated to permanent housing with 35% (1,389 beds) dedicated to temporary housing like emergency shelter and transitional housing.

SO, WHAT?

The national, statewide and local numbers from 2017 Point-in-Time Count are helpful to understand overall trends in the work to end and prevent homelessness. Below are three takeaways to consider from the 2017 numbers.

1) Look at the full picture. The Point-in-Time Count is one of multiple data sources that provide information on progress around housing and homelessness. It is important to also look at the system performance measures which provide the rate of exit to permanent housing, average length of stay in emergency shelter and returns to homelessness. It is also critical to look at homelessness data with other data sources such as the school system. This can be done locally through the UNCC Institute for Social Capital which houses an integrated database, including homelessness and school system data.

At the same time, one of the most important trends from the 2017 Point-in-Time Count on a local, state and national level is the increase in unsheltered homelessness. In Charlotte-Mecklenburg, the 2017 Point-in-Time Count Report shows that 62% of the population surveyed had been homeless for more than a year.

2) It’s still about affordable housing. The high cost of housing and low rate of vacancy in communities across the United States including Charlotte-Mecklenburg, places more and more people at risk of losing their housing. The investment in permanent housing beds like permanent supportive housing and rapid re-housing has contributed to the decrease in homelessness that Charlotte-Mecklenburg has experienced since 2010.

However, with rental costs increasing and potential changes to federal funding for homeless assistance, the work to increase affordable housing – through subsidy and development – is even more critical. To read more about the trends in worst case housing needs, read this 2017 report.

3) We need a system wide approach. The challenges and solutions to housing and homelessness are connected to other areas like employment, healthcare, transportation and childcare. To end and prevent homelessness and increase affordable housing, these areas must be connected and aligned toward a common vision with shared outcomes and priorities. Coordinated Entry / NC 2-1-1, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Housing Our Heroes targeting veteran homelessness, and Housing First Charlotte-Mecklenburg targeting chronic homelessness are three local examples. To close the gap on housing and homelessness for everyone, everyone must play a role.

To get involved in the 2018 Charlotte-Mecklenburg Point-in-Time Count, email Courtney Morton at Courtney.Morton@MecklenburgCountyNC.gov

Courtney Morton coordinates community posts on the Building Bridges Blog. Courtney is the Housing & Homelessness Research Coordinator for Mecklenburg County Community Support Services. Courtney’s job is to connect data on housing instability, homelessness and affordable housing with stakeholders in the community so that they can use it to drive policy-making, funding allocation and programmatic change.