Courtney LaCaria

Housing & Homelessness Research Coordinator

Mecklenburg County Community Support Services

Released last month, A Home for All: Charlotte-Mecklenburg’s Strategy to End and Prevent Homelessness – Part 1: Strategic Framework reflects the community’s work during the past year to develop a comprehensive, transformative strategy to address both housing instability and homelessness. As the first document to be released from this effort, the Strategic Framework provides the roadmap for the work ahead. The framework serves to outline the vision and the major objectives across each of the following nine areas: prevention; shelter; affordable housing; cross-sector supports; policy; funding; data; communications; and long-term strategy.

While any one area of impact and intervention can help chip away at the gaps, the real work must be done on the sum rather than the parts. At the same time, it is essential that we understand each individual part so that we can best position them to complement each other and function effectively as a system. This week’s blog is the second in a new series that seeks to unpack each of the four impact areas in the Strategic Framework aimed at addressing a part of the housing problem: prevention; temporary housing; affordable housing; and cross-sector supports.

This blog, which is focused on temporary housing, covers what temporary housing is (and isn’t), why it is important, what the recommendations in the Strategic Framework entail, and ultimately, what all of this could mean for Charlotte-Mecklenburg.

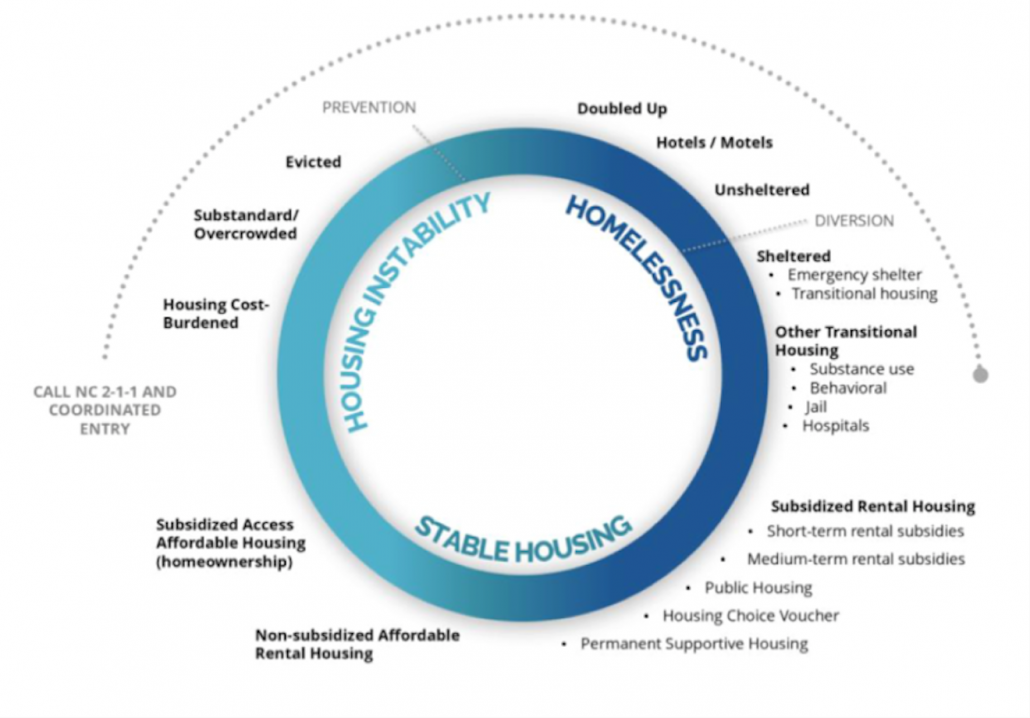

“Temporary Housing” is a category of housing interventions that provides short-term housing assistance to households experiencing homelessness. Using this definition, temporary housing does not just mean shelter. In fact, this intervention exists on a continuum, which is depicted on the graphic above.

The category of temporary housing includes four main types of assistance. Three of the types, emergency shelter; safe haven; and transitional housing, have definitions that are set by the U.S. Department of Housing & Urban Development (HUD). Also, by definition, these three types serve households who meet the HUD definition of “literal homelessness.” The fourth category, labeled “other transitional housing,” captures all other types of transitional housing and can serve households who fall within other definitions of homelessness. The recommendations for temporary housing found within the Strategic Framework cover all temporary housing types. Descriptions are provided below:

Emergency Shelter

An emergency shelter is a facility with the primary purpose of providing temporary shelter for people experiencing homelessness. This category includes shelters that are open seasonally and/or year-round; emergency shelters can be in congregrate (a single space) or non-congregate (private quarters) settings; and also includes vouchers for a household to stay temporarily in a hotel or motel that are paid for by an organization. Emergency Shelter is one of the categories included in the Continuum of Care (CoC)’s Housing Inventory Count (HIC) and, as such, is reported as part of the annual Point-in-Time (PIT) Count to HUD. The following are part considered emergency shelters, per the 2022 HIC.

List of Emergency Shelter Providers (2022 HIC)

Transitional Housing

Transitional housing is a form of temporary housing that is usually coupled with supportive services to facilitate the movement of homeless individuals and families to permanent housing within a reasonable amount of time (usually 24 months or fewer). To be included within the HIC, and, thus reported as part of the annual PIT Count, beds in transitional housing must meet the following critieria: the primary intent of the project is to serve people experiencing homelessness; the project verifies homeless status as part of its eligibility determination; and the clients served by the project are “predominantly homeless.” The following are part considered transitional housing, per the 2022 HIC.

List of Transitional Housing Providers (2022 HIC)

Safe Haven

Safe haven is defined as temporary housing that serves households experiencing homelessness who might be exceptionally “hard-to-reach” with severe mental illness and/or who are experiencing unsheltered homelessness and have been unable and/or unwilling to participate in other types of temporary/permanent housing and/or supportive services. To qualify as a Safe Haven project with the HIC, the following criteria must be met, according to HUD: located in a facility or clearly identifiable portion of a structure or structures; allowing access to residences 24/7 for an unspecified duration; having private or semi-private accommodations; limiting overnight occupancy to no more than 25 persons; prohibiting the use of illegal drugs in the facility; providing access to needed services in a low-demand facility, but not requiring program participants to utilize them; and may include a drop-in center as part of outreach activities. Individuals residing in a Safe Haven facility are considered literally homeless, and enumerated under the category of sheltered homelessness during the Point-in-Time Count. The following is considered a safe haven, per the 2022 HIC.

List of Safe Haven Providers (2022 HIC)

Other Transitional Housing

This category encompasses all other non-emergency, temporary housing types including other forms of transitional housing, or institutional and residential settings such as jails; hospitals; or mental health and/or substance use treatment facilities for people experiencing homelessness.

WHY INCLUDE TEMPORARY HOUSING?

Despite our best efforts, not all forms of homelessness can be prevented. Further, homelessness can literally happen to any one of us. Things like natural disasters – or pandemics – do not discriminate and can uproot entire communities. On a smaller scale, unforeseen tragedies like house fires can evict a family, or a building full of families, and destroy their possessions. And, then there are causes like domestic violence, which may require one or more in a household to flee from their housing for their safety.

The problem is that if and/or when any of these situations occur and there are no immediate resources – people, financial, or otherwise – for a household to call upon, then most likely that household will be both homeless and in need of temporary housing. Therefore, even if a community solves for all the other reasons that a household might end up falling into homelessness, there will always be a need for some form and/or amount of temporary housing in a community. The question for many communities, including Charlotte-Mecklenburg, is how to build a temporary housing system that anyone can access. Once accessed, how can the temporary housing ecosystem be structured such that the need can be effectively and met, and best position a household to obtain permanent housing?

To this end, the group devoted to the temporary housing impact area of the Strategic Framework embraced the following vision: Ensure homelessness is rare, brief, and one-time by building a right-sized and inclusive emergency response system that is able to meet the demand for shelter, temporary housing, and other emergency services.

WHAT ARE THE RECOMMENDATIONS?

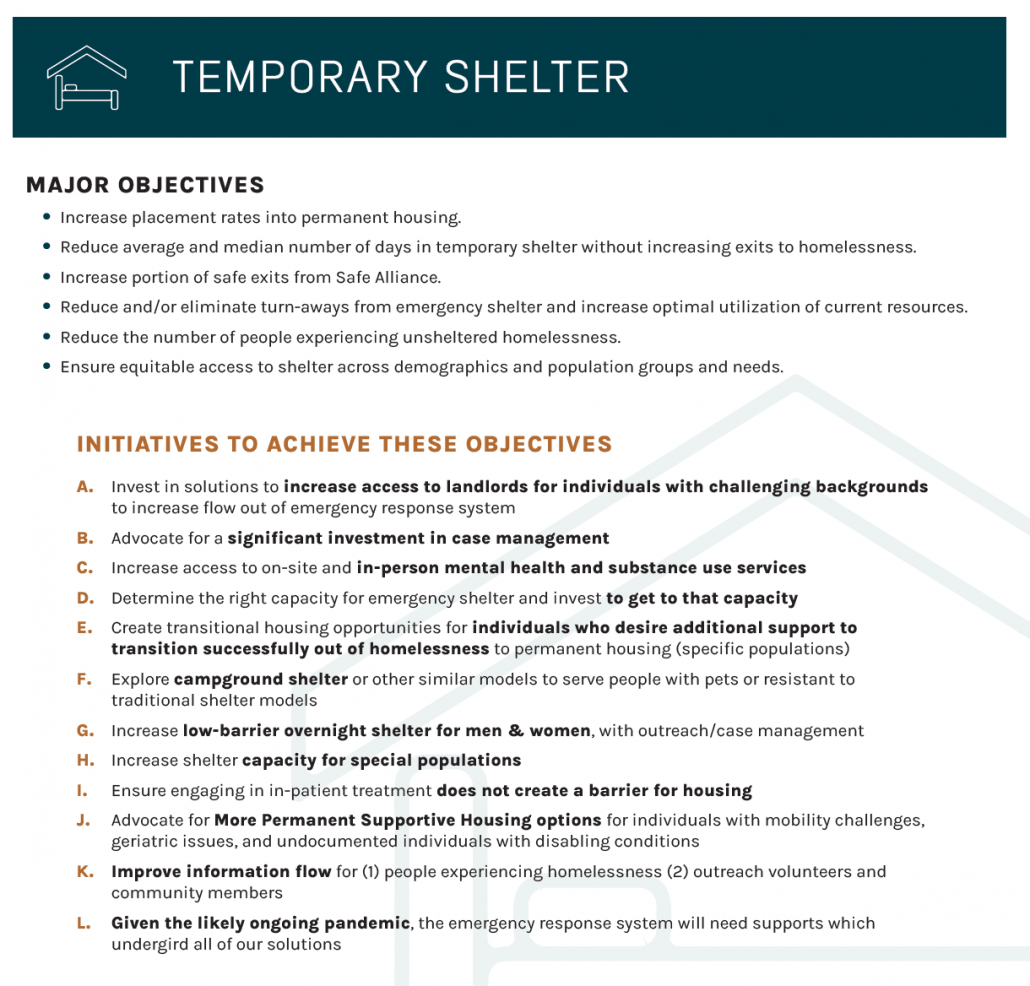

Listed below are the 12 temporary housing recommendations from the Strategic Framework, in priority order. Each of these recommendations have been informed by best practices and research. Included with the name of the recommendation is a description of what the recommendation means and, where relevant, additional context to help illustrate the “why” behind the recommendation.

A. Invest in solutions to increase access to landlords for individuals with challenging backgrounds to increase flow out of emergency response system

This recommendation embodies the first of the Strategic Framework’s core values: addressing historical and structural inequities by employing solutions that rectify or address historical and existing inequities, focusing on individuals and communities with greater barriers and centering racial justice. “Challenging backgrounds” can include individuals with criminal histories, eviction records and/or substance use. Specifically, this recommendation seeks to build upon best practices already underway in community, such as master leases, rent guarantees, risk mitigation funding, and coordinated recruitment efforts. In addition, new practices under consideration include deploying a housing navigator at each major housing organization and rolling out a “common application” to landlords in order to reduce fees for potential tenants. Finally, this recommendation also entails exploring policy changes such as property tax exemptions for participating landlords and “clean slate” legislation.

B. Advocate for a significant investment in case management

Recognizing that more individualized support and consistency in case management is critical to both obtaining and retaining housing, this recommendation calls for increasing the number of case managers available throughout the emergency response system, thereby lowering caseloads. In addition, this recommendation seeks to improve compensation for case managers; expand access to training and skill development, including trainings focused on trauma-informed care, Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), and implicit bias; provide support for vicarious trauma; and explore the potential of leveraging peer support specialists for individualized care.

C. Increase access to on-site and in-person mental health and substance use services

To increase access to services, this recommendation seeks to embed mental health and substance use services on-site at homeless service providers, maximizing existing services and expanding partnerships, where possible. In addition, peer support specialists, who can help build trust to support individuals experiencing homelessness to engage in mental health and substance use services, and potentially continue with individuals once in housing, would also be located on-site.

D. Determine the right capacity for emergency shelter and invest to get to that capacity

According to “turn away” data, which refers to individuals who seek emergency shelter but, due to a lack of capacity, are “turned away,” Charlotte-Mecklenburg does not have a sufficient number of emergency shelter beds to meet the need for them. Emergency shelters employ a multiple approaches to improve flow through the emergency shelter system as well as maximize capacity. Despite these measures, there are still individuals who need emergency shelter, but cannot access it; furthermore, this may worsen as the economic conditions worsen. In alignment with the second core value of the Strategic Framework, this recommendation seeks to expand access to and availability of inventory and resources. To determine the right capacity for the emergency shelter system, this recommendation would develop and then test a formula that assesses opportunities for the system to decrease inflow into shelter; increase outflow out of shelter; and to what extent expansion of beds is required and best executed.

E. Create transitional housing opportunities for individuals who desire additional support to transition successfully out of homelessness to permanent housing (specific populations)

Transitional housing is a type of temporary housing that can be helpful for specific populations who need additional support to successful transition out of homelessness. This recommendation focuses on ensuring 100% safe exits for households fleeing domestic violence, recognizing that the trauma of domestic violence and additional transition time may be needed to find permanent housing for survivors. In addition, this recommendation could support individuals with severe and persistent mental illness (SPMI) who are awaiting permanent, subsidized housing; and households with significant barriers to employment and housing, including individuals who are criminal-justice involved; emerging adults (18 to 22 years old) who have exited Juvenile Justice Youth Development Centers and have no housing options upon release; and individuals exiting in-patient substance use treatment.

F. Explore campground shelter or other similar models to serve people with pets or resistant to traditional shelter models

Based upon feedback from focus groups with individuals with lived experience of housing instability and homelessness, this recommendation explores the possibility of alternative, temporary structures that could serve as an “emergency shelter” to individuals who do not want to enter a “traditional” emergency shelter for various reasons. This includes, but is not limited to: pallet structures; legalized encampment; and/or other non-congregate models. For this type of model to be successful, supports would need to be provided on-site as well as access to bathroom, shower and laundry services, while also remaining low-barrier.

G. Increase low-barrier overnight shelter for men & women, with outreach/case management

While our community’s traditional shelters have “assigned beds” that provide greater stability, some individuals prefer the lower-structure setting of an overnight shelter. Beds are provided on a nightly basis and individuals can access the shelter when they choose, without the expectation of staying every night. During the pandemic, an overnight, low-barrier shelter opened for men, operated with special COVID-19 funding; this funding expires in June 2022. This recommendation seeks to continue this COVID-19 innovation as well as expand to serve all populations experiencing homelessness coupled with outreach/case management.

H. Increase shelter capacity for special populations

In addition to expanding emergency shelter capacity for everyone who needs it in the community, this population focuses on ensuring adequate capacity exists for special populations who have specific needs that might require additional support or infrastructure. Populations include: shelter for single-father families; workforce-focused population; recovery-focused shelter (e.g. individuals exiting treatment); and/or sober shelter for individuals who desire this form of care.

I. Ensure engaging in in-patient treatment does not create a barrier for housing

According to current policy established by the U.S. Department of Housing & Urban Development (HUD), in-patient treatment can become a barrier for supportive housing programs. Therefore, this recommendation seeks to explore advocacy opportunities and local solutions such as locating housing navigators with in-patient treatment programs, local sources of flexible funding, and continued collaboration between organizations to find individualized solutions for individuals who need in-patient treatment before, or during their tenure in supportive housing.

J. Advocate for more Permanent Supportive Housing options for individuals with mobility challenges, geriatric issues, and undocumented individuals with disabling conditions

This recommendation focuses on individuals who have gotten “stuck” in the emergency shelter system and whose needs require additional support beyond which the current emergency shelter can support. In addition to creating a housing pathway for those who currently have no options, this recommendation will help the emergency response system be better prepared to serve an aging homeless population and will positively impact the community’s hospital systems and Permanent Supportive Housing programs.

K. Improve information flow for (1) people experiencing homelessness (2) outreach volunteers and community members

Reflecting the third core value of the Strategic Framework: coordinating systems to ensure that they are easy to navigate for the individuals who need them, this recommendation calls for the creation of an effective mechanism for the wider community to know how to help someone engage with individuals experiencing unsheltered homelessness and connect them to appropriate services. Such a mechanism would help grassroots volunteers not only build relationships and provide food individuals experiencing homelessness, but also connect them with housing. In addition, this recommendation seeks to increase and coordinate support for the groups who provide street outreach; improve the Coordinated Entry/NC 2-1-1 experience and results for individuals seeking immediate support; and create a pathway for literally homeless individuals to rapidly access services.

L. Given the likely ongoing pandemic, the emergency response system will need supports which undergird all of our solutions

Recognizing that some of the changes instituted in response to the pandemic will need to remain either permanent or able to be recalled quickly, this recommendation seeks to ensure that there is sufficient community-provided isolation and/or quarantine space and staffing; access to on-site testing and vaccine resources; and funding at the levels needed to operate in a pandemic (e.g. cleaning, hazard pay) and/or other disaster.

SO, WHAT

Just as with investing in prevention-related solutions, it is important to note that a focus on temporary housing does not mean a lack of focus (or investment, research, etc.) on the other areas of the housing continuum. It’s not a zero-sum game. In fact, for any or all of this to work, a community’s efforts must be a both/and.

Last week, HUD released the 2021 Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress, which contains the national Point-in-Time Count data from January 2021. According to the report, sheltered homelessness (encompassing emergency shelter, transitional housing, and safe haven) decreased 8% (28,260 people) from the previous year. In other words, when comparing sheltered homelessness pre-pandemic to in-the-middle-of-a-pandemic, the number of households experiencing sheltered homelessness went down, overall.

Or did it?

Because of the way the Point-in-Time Count is conducted, this decrease does not necessarily mean that homelessness actually decreased. It has more to do with how sheltered homelessness is defined, and thus, enumerated; and how each of the other forms/definitions/types of homelessness are not. For example, if someone is experiencing homelessness on the night of the Point-in-Time Count, but not within a facility that meets the definition set by HUD, then they are not counted for the purposes of the Point-in-Time Count. Similarly, shelters who have had to close, or reduce their number of beds due to COVID-19, will then have fewer individuals within their facilities to count.

In contrast to the national numbers, sheltered homelessness in Charlotte-Mecklenburg increased from 1,390 individuals in emergency shelter, transitional housing, and safe haven to 1,672 total individuals from January 2020 to January 2021. As with the example provided above, most of the increase is attributable to the expansion in emergency shelter capacity; in fact, the number of individuals in transitional housing decreased by 42. In response to COVID-19, eight new emergency shelter projects, which included those funded for non-congregate space in hotels and motels, were in opened by the time of the 2021 Point-in-Time Count.

At the same time, there was also an increase in unsheltered homelessness, from 214 individuals in January 2020 to 269 individuals in January 2021. The increase in sheltered homelessness coupled with the increased in unsheltered homelessness would suggest there is an increase in need for temporary housing in Charlotte-Mecklenburg. And, again, it only serves to underscore the real problem, and the only real solution to housing instability and homelessness: more permanent, affordable housing. Temporary housing, although not sufficient on its own, is absolutely a key part of the system that will help us ensure A Home For All.

SIGN UP FOR BUILDING BRIDGES BLOG

Courtney LaCaria coordinates posts on the Building Bridges Blog. Courtney is the Housing & Homelessness Research Coordinator for Mecklenburg County Community Support Services. Courtney’s job is to connect data on housing instability, homelessness and affordable housing with stakeholders in the community so that they can use it to drive policy-making, funding allocation and programmatic change.