Courtney LaCaria

Housing & Homelessness Research Coordinator

Mecklenburg County Community Support Services

Last week, A Home for All: Charlotte-Mecklenburg’s Strategy to End and Prevent Homelessness – Part 1: Strategic Framework was released. The Strategic Framework reflects the community’s work during the past year to develop a comprehensive, transformative strategy to address both housing instability and homelessness. As the first document to be released from this effort, the Strategic Framework provides the roadmap for the work ahead; serving to outline the vision and the major objectives across each of the following nine areas: prevention; shelter; affordable housing; cross-sector supports; policy; funding; data; communications; and long-term strategy.

The Strategic Framework is only one part of the overall strategy, but perhaps the most important. This is why 9 workstreams held standing meetings, and over 250 individuals in the community were engaged directly. A framework explains what we are doing, how we expect to do it, and how we will know if we did what we said we would. It took a year to develop, but all of that time was needed in order to meet the goal of ending and preventing homelessness and ensuring that everyone has access to affordable housing and the resources to sustain it.

Addressing the interrelated problems of housing instability and homelessness requires a comprehensive and coordinated approach, with a focus on changing systems and structures. While each individual area of impact and intervention can help chip away at the gaps, the real work must be done on the sum, rather than the parts. At the same time, it is essential that we understand each individual part so that we can know how to best position them to complement each other and function effectively as a system.

Therefore, the purpose of this new blog series is to unpack each of the four impact areas in the Strategic Framework aimed at addressing a part of the housing problem: prevention, shelter, affordable housing and cross-sector supports. This week’s blog is focused on the area of prevention, including what it is, why it is important, what the recommendations in the Strategic Framework entail, and ultimately, what all of this could mean for Charlotte-Mecklenburg.

WHAT IS PREVENTION?

“Prevention” is defined as a category of assistance that targets households “upstream” from homelessness who are facing housing instability but have not yet lost their housing. In many instances, this slide into homelessness is avoidable with the right interventions.

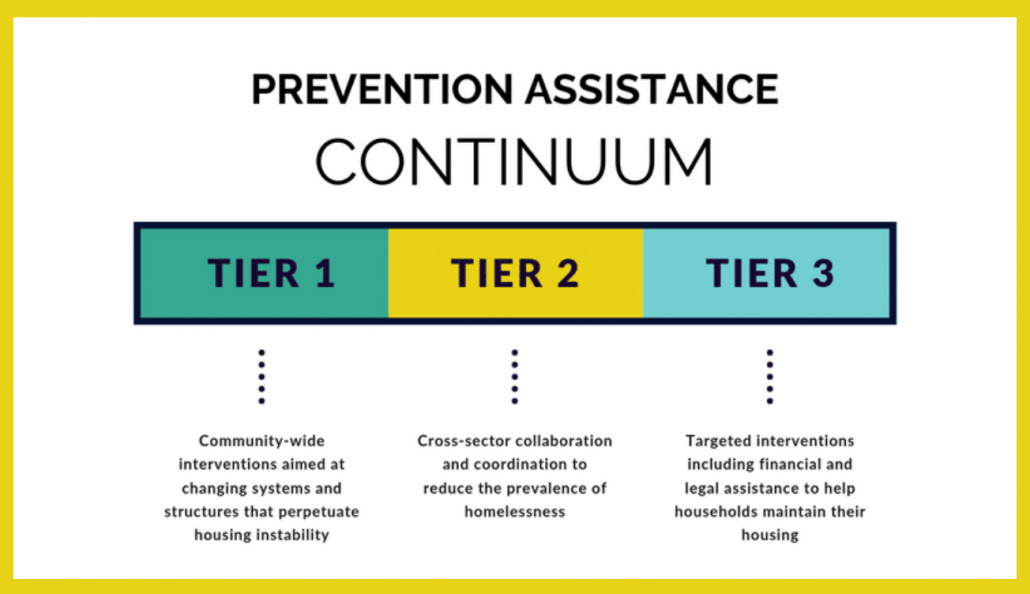

Using this definition, prevention assistance exists on a continuum: assistance can be administered prior to the loss of housing as well as after households exit into permanent housing to help them sustain it.

Prevention includes three tiers of assistance:

- Community-Wide Interventions aimed at changing systems and structures that perpetuate housing instability (more affordable housing, policy change, equity lens)

- Cross-Sector Collaboration And Coordination to reduce the prevalence of homelessness (discharge planning, linking services)

- Targeted Interventions including financial and legal assistance to help households maintain their housing (critical home repair, subsidies, landlord/tenant mediation)

In its simplest form, prevention encompasses any type(s) of intervention that help households stay housed. With that in mind, prevention-related recommendations will naturally overlap with recommendations in other impact areas in the Strategic Framework that have similar aims, including provision of affordable housing and/or cross-sector supports.

WHY INCLUDE PREVENTION?

Prevention is smart and strategic for communities. It is the most efficient use of all the resources at a community’s disposal; in short, it saves money. Prevention protects households. It reduces trauma. It preserves a path to building wealth. It enables the shelter system to maximize precious beds for the individuals who most need them. And, in the wake of COVID-19, it has come to be known to safeguard public health. Prevention just makes good sense.

But research and intervention funding have historically been directed at planning interventions for people who have already become homeless. It really wasn’t until the pandemic that prevention to keep individuals and families housed was embraced and funded on a larger scale, including at the federal level. Prior to the pandemic, however, Mecklenburg County had already begun investing in prevention as a concept and as an intervention.

In 2020, Mecklenburg County Community Support Services (CSS) launched a community project called “Evaluate Upstream: Optimizing the Homelessness Prevention Assistance System” focused on homelessness prevention. The project was funded by a Continuum of Care (CoC) planning grant from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). This project, which built upon previous work by the CSS to raise awareness about as well as organize prevention assistance as a system, provided a unique opportunity to invest in prevention planning “upstream” from homelessness and, more importantly, to do so in a way that focused on what is working or has worked for households who have experienced housing instability. The results of this work, captured within the Evaluate Upstream Blueprint were used as the starting place for what became the recommendations for prevention in the Strategic Framework.

WHAT ARE THE RECOMMENDATIONS?

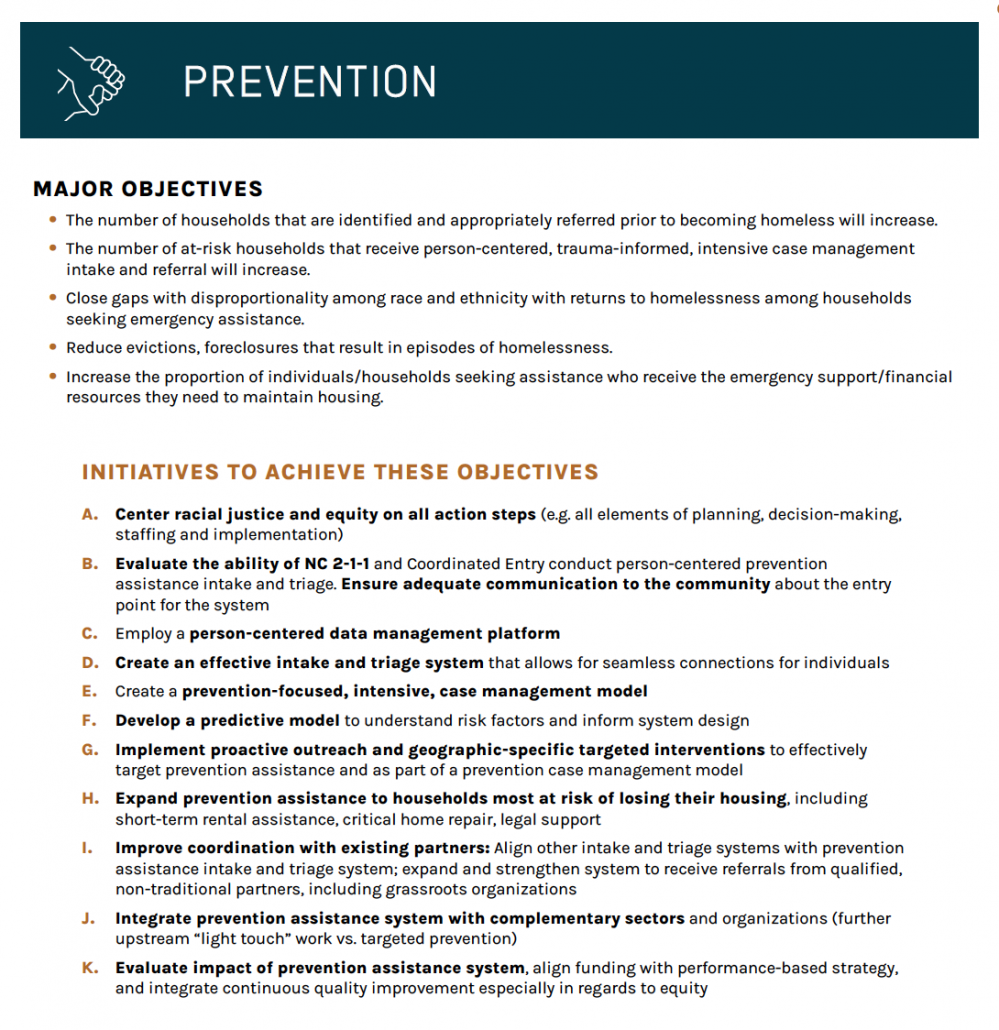

Listed below are the 11 prevention recommendations from the Strategic Framework, in priority order. Each of these recommendations have been informed by best practices and research. Included with the name of the recommendation is a description of what the recommendation means and, where relevant, additional context to help illustrate the “why” behind the recommendation.

A. Center racial justice and equity on all action steps (e.g. all elements of planning, decision-making, staffing and implementation)

This recommendation is really a through line that permeates all aspects of the framework. In fact, a focus on equity and parity overlaid the work of the nine workstreams. Addressing historical and structural inequities was identified as the first of four core values undergirding the recommendations in the Strategic Framework. Additionally, the Evaluate Upstream Blueprint recommended applying an equity lens when considering any recommendation. Examples of this include engaging individuals with lived experience of housing instability and homelessness, and who reflect the demographics of people with lived experience of housing instability and homelessness, into all elements of planning; decision-making; staffing; and implementation. Other ways to center these include regularly assessing the impact of equity-based decision-making, and making corrections to program design to ensure equitable outcomes; ensuring strategies, communication efforts and funding decisions create opportunity and choice for all individuals; ensuring the implementation of all processes prevent predatory or discriminatory practices from occurring; and enabling an array of community-based organizations, including non-traditional partners, who are best able to effectively reach into historically marginalized communities to be able to provide prevention services and/or resources to maximize the impact of any work.

B. Evaluate the ability of NC 2-1-1 and Coordinated Entry to conduct person-centered prevention assistance intake and triage. Ensure adequate communication to the community about the entry point for the system

Together, NC 2-1-1 and Coordinated Entry comprise the system portal that serves as the entry point (or input) for households experiencing housing instability and homelessness, with the goal of connecting households who are seeking assistance to an available shelter or other housing resources. At the output end, participating organizations agree to accept referrals from this single portal and align prioritization of their resources accordingly. As a system-focused intervention, Coordinated Entry helps the community to both order available resources for the most vulnerable households and to identify gaps and shortages in housing resources. However, it has become apparent that there are also gaps in how the current system is functioning. A study of NC 2-1-1 conducted as part of Evaluate Upstream found that the “current intake, screening and Coordinated Entry pipeline operates more like a sieve that permits leakage of populations who are in dire need… [Further,] …there is no current mechanism for consistent identification, tracking and follow up with individuals and families who have received referral information; there are insufficient “warm handoffs” of households to homelessness prevention programs and services; and there is no methodology for assessing the effectiveness and impact of those resources to which at-risk callers are referred by NC 2-1-1 operators.” In addition, UNCC Urban Institute is in the process of completing a multi-year evaluation of Coordinated Entry. Therefore, next steps must involve incorporating lessons learned from these studies; they must also embody the second core value of the Strategic Framework: “Coordinate systems to ensure they are easy to navigate for the households who need them.”

C. Employ a person-centered data management platform

A person-centered data management platform enables cross-sector (healthcare, benefits, etc.) referrals and case coordination so that the person accessing resources need not have to enroll and re-enroll in multiple systems and/or databases to access resources. This also shifts the burden so that the systems do the work; by doing so, this streamlines the process for the person seeking assistance. The resources of an individual or family in crisis simply do not come close to the resources of a service provider. Further, if done well, this shift could also mean that those same systems preserve some of their own resources simply by better sharing information with each other.

D. Create an effective intake and triage system that allows for seamless connections for individuals

Integrating the findings from “B” above, this step involves the work to implement the changes necessary. In addition to simply functioning effectively and as intended, it is critical that the intake and triage system be aligned with intake and triage systems in other sectors that might serve the same households, whether currently or prospectively.

E. Create a prevention-focused, intensive, case management model

The need for this type of model was underscored by individuals with lived experience of housing instability and homelessness. Having a case manager or similar navigator is essential to help navigate the complex and complicated web of prevention-related resources. Identified components include follow-up and ongoing case management supported by Housing First; Employment First; trauma-informed and person-centered practices; and shared data collection, referrals, and reporting.

F. Develop a predictive model to understand risk factors and inform system design

Using cross-sector data, the goal of this recommendation is to develop a predictive model that can identify the risk factors that might lead to homelessness, and then use that information to inform system design; resource allocation; prioritization; and policymaking. This recommendation builds upon the successes of similar efforts, including the work in Los Angeles that leveraged data across multiple systems, including mainstream County services, to target prevention resources

G. Implement proactive outreach and geographic-specific targeted interventions to effectively target prevention assistance and as part of a prevention case management model

Being reactive and distributing resources to households seeking assistance means that the household first must have access to both the information and the means with which to seek assistance. Instead, this type of intervention takes a step toward those households in need, proactively targeting households that might be most risk of losing their housing and therefore in need of assistance. This type of intervention leverages the model developed in recommendation “F” above, as well as other tools like site mapping as developed by the Urban Institute (Washington, DC) in response to COVID-19. Communities can use this mapping tool, “Where to Prioritize Emergency Rental Assistance to Keep Renters in Their Homes” to identify neighborhoods in which low-income renters might be at a higher risk of experiencing housing instability.

H. Expand prevention assistance to households most at risk of losing their housing, including short-term rental assistance, critical home repair, legal support

This recommendation covers multiple types of prevention assistance, ranging from rental subsidies, to critical home repair, to legal support. The common denominator as a prevention assistance intervention is the target population: households who have not yet lost their housing. Other examples can include flexible cash grants to low-income households; exploring, identifying, and expanding new and existing sources of public and private funding at all levels; creating new subsidy models that are flexible in range and/or tenure; and increasing employer-based targeted income supplements.

I. Improve coordination with existing partners: Align other intake and triage systems with prevention assistance intake and triage system; expand and strengthen system to receive referrals from qualified, non-traditional partners, including grassroots organizations

This recommendation embodies two of the four core values of the Strategic Framework: coordinating systems to help individuals better navigate them, as well as changing the system to sustain long-term impact by enacting policy; structural; and process-related

Changes, to create an environment that facilitates and sustains the changes necessary.

Cross-sector collaborations are essential to provide holistic and comprehensive support for households experiencing housing instability and homelessness. This also means that the system must be inclusive, ensuring that all providers (including non-traditional partners and grassroots organizations) are able to connect.

J. Integrate prevention assistance system with complementary sectors and organizations (further upstream “light touch” work vs. targeted prevention)

This recommendation is both about the prevention system, itself, and the individual parts. As a system, it is important to appropriately situate the prevention assistance between the further “upstream” work taking place to address opportunity and poverty (such as that by Leading on Opportunity), and the homelessness services system downstream. This means, at bottom, identifying and linking recommendations and promoting outcomes that can be shared across this spectrum. It also means alignment of the disparate parts by employing concepts that bridge the complementary sectors and organizations, including taking a multi-generational approach; driving economic opportunity; embracing Housing First and Employment First; and testing for cost-effectiveness. Finally, this means providing education to help raise awareness about the opportunities and benefits for people who might qualify for prevention assistance.

K. Evaluate impact of prevention assistance system, align funding with performance-based strategy, and integrate continuous quality improvement especially in regards to equity

Finally, it is critical that all interventions, separately and together, be evaluated. This includes aligning funding with a performance-based strategy; educating funders and stakeholders on goals and progress; and integrating continuous quality improvement.

SO, WHAT

It is important to note that a focus on prevention can mean a lack of focus (or investment, research, etc.) on other areas of the housing continuum. It’s not a zero-sum game. In fact, for any or all of this to work, a community’s efforts have to be a both/and. There are complementary effects: focusing on prevention actually helps solve for problems with shelter capacity, for example.

Although prevention is still relatively new as a homelessness intervention, it has gained steam during the pandemic. This also means that there is more data available to support this shift in focus. In September 2020, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued a nationwide eviction moratorium in residential evictions for nonpayment of rent. In addition, Congress passed two bills that collectively appropriated over $46 billion in emergency rental assistance. The Emergency Rental Assistance program, specifically, has proven to be a central mitigating force in both the fight again evictions and the coronavirus. Rental and utility assistance funded by the federal COVID-19 relief packages, have since been expanded by cities and states.

While the combination of the eviction moratoria and rental assistance staved off a tsunami of evictions, these measures were temporary: the moratoria have generally been lifted and the emergency rental assistance that was funded as part of COVID-19 relief has been expended.

In June 2021, a bipartisan group of senators reintroduced the Eviction Crisis Act (ECA), which had first been introduced in 2019. The ECA seeks to create a permanent, $3 billion Emergency Assistance Fund that would be able to evaluate and expand interventions that support low-income households facing housing instability.

In conclusion, and said simply, more prevention assistance is needed. Just as more permanent affordable housing is needed. And, if implemented effectively as a system, more prevention assistance may also help close the gap in the number of permanent, affordable housing units that Charlotte-Mecklenburg needs to ensure A Home for All.

SIGN UP FOR BUILDING BRIDGES BLOG

Courtney LaCaria coordinates posts on the Building Bridges Blog. Courtney is the Housing & Homelessness Research Coordinator for Mecklenburg County Community Support Services. Courtney’s job is to connect data on housing instability, homelessness and affordable housing with stakeholders in the community so that they can use it to drive policy-making, funding allocation and programmatic change.