Ken Szymanski

Executive Director, Greater Charlotte Apartment Assocation

Growing up in the 1960’s like I did, you had to be living under a rock not to be affected by the ultra-compelling and ultra-unfair conditions of racial discrimination and racial segregation in U.S. cities.

The cause of those who fought against these inequities was gripping and undeniable – the folks who stood up were on the right side of the issue, even at a time when not many were willing to stand up.

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated on April 4, 1968. And the Federal Fair Housing Act was enacted on April 11, 1968 – one week later. No coincidence.

We celebrate April as Fair Housing Month every year; here in 2018, we observe, celebrate, and re-focus on the spirit and complex compliance aspects of the Act for its 50th Anniversary. Today, Fair Housing law and debates are much more complex than back in the ‘60’s. It is important that we continue to understand new components that become part of the work to ensure fair housing including: disparate impact, emotional support animals, transgender rights, reasonable accommodation of disabilities, and source of income. These and others were pretty much unheard of 50 years ago.

Over the years, society has become more multifaceted, but the bedrock principle of unfair treatment and being denied shelter for the wrong reasons resonates as strongly as ever today. These are riveting issues, and if you care about cities and the people who reside in them, you need to be a student of Fair Housing.

EVICTIONS AND FAIR HOUSING

Evictions can result from the failure to uphold and abide by Fair Housing legislation. The April 7 New York Times article highlights the recently released work of Matthew Desmond, Pulitzer Prize winning author of “Evicted“. Desmond released a website called the Eviction Lab with over 83 million eviction records mapped across the United States. Charlotte ranks 21st out of 100 large cities in the United States for highest evictions.

Last month, UNC Charlotte released the report, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Evictions Part 2: Mapping Evictions, revealing a geospatial pattern in which evictions are concentrated in certain neighborhoods and echoing other patterns related to wealth, education, housing and health. These patterns are reflective of a history of policies and practices that have had discriminatory effects and disproportionately impacted households of color and households living in poverty.

I spent a fair amount of my formal training studying neighborhood segregation and the dynamics of racial change in American cities. These dynamics – like it or not – are still very much in play here in Charlotte and elsewhere.

Below are key quotes that have stood out to me from researchers and academicians over the past 50 years

Racial segregation (or ghettoization) is ‘the urban problem,’ and some modification of historic patterns of racial segregation in metropolitan housing is necessary to achieve reasonably efficient solutions to an ever increasing array of related problems.

Residential segregation prevails regardless of the relative economic status of the white and Negro residents. It occurs regardless of the character of local laws and policies, and regardless of the extent of other forms of segregation or discrimination.

We need to be aware that segregation is not going away by itself. And that it hasn’t been solved by the growth of the black middle-class, the softening of white attitudes on race, or the laws that prohibit racial discrimination in housing. These are all factors that might have had a positive effect on segregation, and the assumption has been that they must have had an effect. But it’s very important to realize that they have not.

SO, WHAT

So, let’s think back to 1968 and recall not only the inspiring leadership of Dr. King, but also that of NAACP leader Roy Wilkens, Urban League leader, Whitney Young, Supreme Court Justice, Thurgood Marshall, and many others.

And let’s think not only of urban segregation, but also related matters of substandard housing, overcrowding, and the limited buying power of low wages.

We have come a long way. In my (somewhat lengthy) career, I’ve gotten to witness progress first-hand in the low-income neighborhoods of San Antonio, Texas; Toledo, Ohio; Nashville, Tennessee; and Albany, New York.

As housing providers and as a society, we still have a long way to go with equal housing opportunity. Fifty years later, the “why” is still the same. It’s all about respect and human dignity.

You can become a student of Fair Housing and help others. Please follow the links below to two upcoming 3-hour training sessions on April 19, sponsored by the Greater Charlotte Apartment Association. You can register for either the morning or the afternoon session.

Morning Session (9am – 12pm)

Afternoon Session (1:30pm – 4:30pm)

If you want to learn more, below are terms that are used to explain Urban Residential Segregation

Click the box to learn more.

Poverty

Generally understood as living without the basic necessities of life – food, clothing or housing. Poverty is measured differently around the world; one is considered in “poverty” if their income is less than the poverty threshold. In the United States, the U.S. Census Bureau establishes a poverty threshold. In 2017, the poverty threshold for a family of four is $24,944.

Legal Barriers

Legal constraints that might serve as a barrier to prevent public policy and urban planning solutions.

Social Incompatibility

A criterion that can be applied in practice to effectively exclude sectors of a population.

Discriminatory Real Estate Practices

Real estate practices that have historically and continue to discriminate against specific populations. In the United States, this includes the practice of redlining which is further defined below.

Discriminatory Banking Practices

Practices by financial institutions that have and continue to discriminate against specific populations based upon criteria such as geographic neighborhood and credit status. These include predatory lending practices that led to the housing crisis in 2008 and had a disproportionate impact on racial minorities.

Redlining

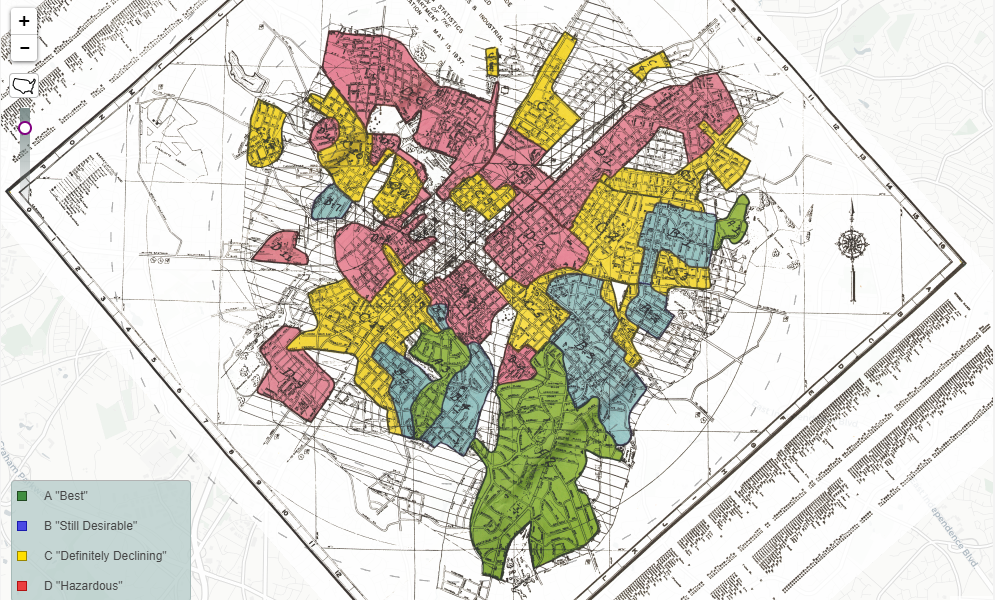

A discriminatory practice in real estate also known as “mortgage discrimination” where services are denied to residents of certain areas based upon racial or ethnic composition of those areas. This came into existence in 1934 with the National Housing Act of 1934. “Residential security maps” were created to outline the level of security for real-estate investments in cities across the United States. The high-risk areas were outlined in red; many minority households who were “redlined” on the maps were denied mortgages by banks, which impacted those families and neighborhoods.

Mapping Inequality is a site that allows you to view more than 150 interactive maps and area descriptions to show the practice and impact of redlining, including Charlotte, North Carolina.

Disinvestment

The systematic withdrawal of capital and neglect of public services by a municipality in a specific area of the community. Neighborhoods can experience cycles of disinvestment followed by gentrification and subsequent dislocation of minority households.

White Flight

Coined during the 1950s and 1960s to refer to the departure of whites from neighborhoods that were increasingly or predominantly populated by minorities to suburbs.

Preference for the Group

Refers to the allegiance to the minority community and culture.

Land Use Barriers & Buffers

Conditions that exist to help or hinder land use in relation to a housing project or plan. These can include the physical division of an established community or conflicts with land use plans, policies and regulations. A city’s zoning ordinance is a primary way that land use regulations are established and managed.

Ken Szymanski has been in the housing and community development fields for 42 years, including 31 years in Charlotte. His formal training is in city planning, land economics, and public administration. He is executive director of the Greater Charlotte Apartment Association.