Courtney LaCaria

Housing & Homelessness Research Coordinator

Mecklenburg County Community Support Services

Over the last two weeks, the Building Bridges blog has focused on the recent shift in attention, energy, and investment in expanding affordable housing solutions, especially in response to COVID-19. These efforts include the 2025 Charlotte-Mecklenburg Housing & Homelessness Strategy (CMHHS), launched in April to address the full housing continuum – from homelessness to households experiencing housing instability.

Last week’s blog post discussed the role of benchmarking local progress with that of peer communities as solutions are developed and/or outcomes are evaluated; and describes how Charlotte-Mecklenburg compares with five peer communities on key housing and homelessness metrics. The post just prior focused on the essential documents to read to fully understand, and therefore address, the entire “housing and homelessness iceberg.”

Strategic housing plans are not new. In 2006, Charlotte-Mecklenburg launched “More than Shelter: a 10-year implementation plan to end and prevent homelessness.” The “ten-year plan” model was also adopted by other communities across the United States. Having not met the goal at the end of ten years, many communities have released revisions and/or new iterations, often with shorter time frames. Some communities have no advertised plan. In response to recent funding associated with COVID-19, however, even communities without plans have been forced to think about how best to appropriate this historic infusion of housing dollars from a system-level view. By October 1, 2021, the 2025 Charlotte-Mecklenburg Housing & Homelessness Strategy plans to develop and launch a new, multi-year, comprehensive plan to end and prevent homelessness in the community.

This week’s blog post is focused on the elements that make a “good” housing strategic plan; highlights examples from other communities; and discusses what this could ultimately mean for Charlotte-Mecklenburg.

QUANTIFIES THE COST TO IMPLEMENT & SUSTAIN

To execute a plan, it is critical that communities know what it will cost to both implement recommendations and to sustain them. What is the overall price tag? What are the costs for individual recommendations? Quantifying the cost brings the problem out of the nebulous and makes it concrete. It transforms the problem into something measurable and solvable.

In addition, plans can quantify the cost of inaction. This includes more than the financial impact. What are the negative ramifications to the economy if homelessness increases? How does a lack of housing supply affect the cost to provide other services, including shelter and healthcare? More importantly, what is the human cost that results from a lack of opportunity?

The examples highlighted below are from housing strategic plans with cost included:

Central Ohio’s Securing Resiliency Strategic Plan

Released in November 2020 by the Affordable Housing Alliance of Central Ohio (AHACO), the goal of the three-year Securing Resiliency Strategic Plan is to cut Franklin County’s 54,000-household affordability gap in half by 2028. The total price tag assigned to the plan’s three main categories (develop affordable housing, support homeownership and stabilize renter households) is $154.3 million. According to the 2021 Winter Scorecard, over $226 million has been raised; and the affordability gap has been reduced by 3,040 units.

This community was identified in last week’s blog post as a peer community for Charlotte-Mecklenburg.

A Toolkit to Close California’s Affordable Housing Gap: 3.5 million homes by 2025

In 2016, the McKinsey Global Institute, the business and economics research arm of McKinsey and Company, released a toolkit on solutions to help close the affordability gap in California. The toolkit provides estimates for both the lost economic output as a result of the housing shortage and the financial impact of specific interventions.

ADDRESSES THE FULL SPECTRUM OF NEED

To be effective, a good housing plan must be comprehensive, attending to the full spectrum of need, from homelessness to housing instability. If the plan limits its view to only what is in plain sight, it will only scratch the surface of the problem, and as a result, waste limited time and resources while ignoring what’s below the waterline. Expanding the view helps everyone.

For example, when prevention resources are employed upstream to households facing housing instability, there are positive, downstream impacts. Prevention reduces inflow into homelessness, which enables the shelter system to be optimized to do what it is supposed to do: ensure that anyone who is facing a housing crisis has access to a safe space so that they can quickly stabilize, and then regain housing. Conversely, when there is an adequate housing supply for everyone at all price points, housing instability and homelessness decrease.

A full spectrum applies to both the interventions (prevention, emergency shelter, permanent, affordable housing and cross-sector supports), and the types of households and populations experiencing homelessness (veterans, chronic homelessness, families, youth, and single adults). It also includes ensuring that the needs of households all levels of Area Median Income (AMI) are met. Currently, the largest need is for households with income at or below 30% of AMI ($17,700 for a single individual and $26,500 for a family of four).

It is difficult to find a housing plan that is truly comprehensive enough to address the full housing and homelessness iceberg. Highlighted below are two examples, each with elements of a housing strategic plan that attend to multiple categories of need:

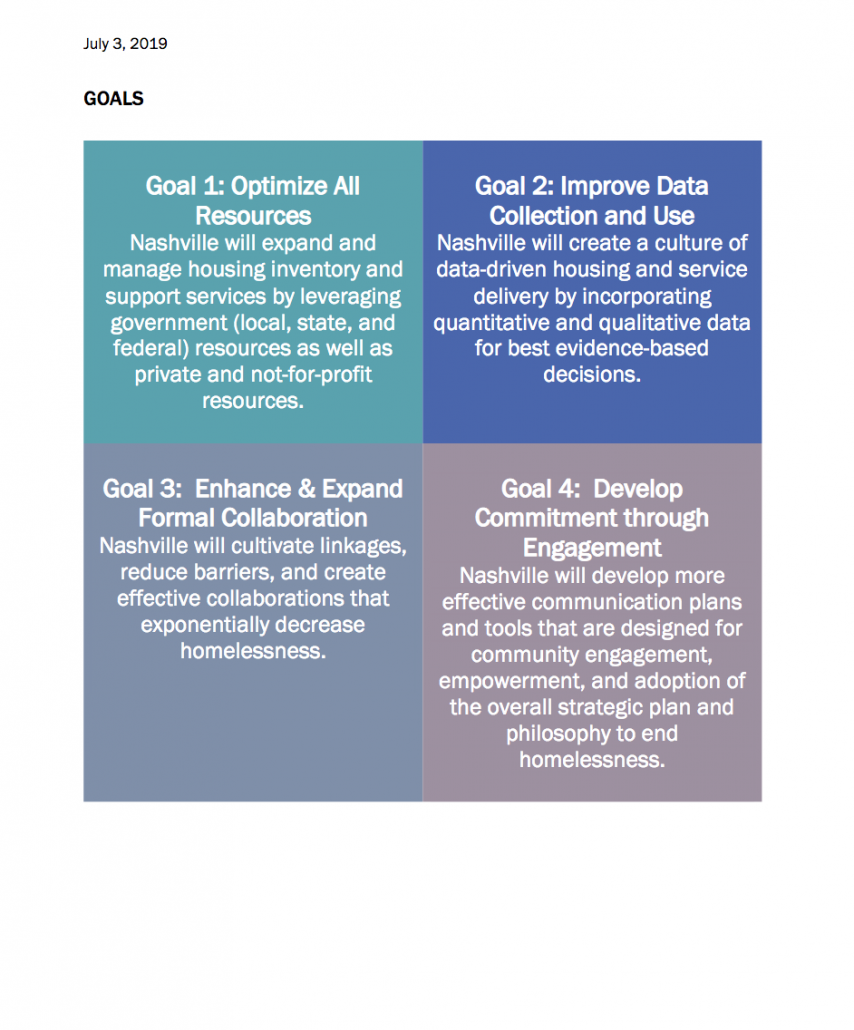

HOMELESSNESS PLANNING COUNCIL STRATEGIC COMMUNITY PLAN

Released in 2019 by the Nashville-Davidson County Continuum of Care, the goal of the three-year strategic community plan is to reduce homelessness by 25%, and ensure that any person who falls into homelessness is able to regain housing in fewer than 90 days.

The plan includes all population and household types experiencing homelessness, as well as especially vulnerable populations, such as domestic violence survivors; multi-generational families; single fathers accompanied with their minor children; and individuals re-entering the community from the justice system.

In addition the plan describes how it plans to build upon and integrate other housing-related initiatives and plans, including “Under One Roof 2029,” which focuses on increasing affordable housing in the community.

This community was identified in last week’s blog post as a peer community for Charlotte-Mecklenburg.

HOUSING FOR EQUITY: AN ACTION PLAN FOR PHILADELPHIA

Released in 2018 by the City of Philadelphia, the five-year action plan addresses needs both upstream and downstream, from eviction prevention to homelessness and affordable housing creation and preservation. In addition, the plan attends to strengthening alignment with cross-sector supports, with a specific focus on healthcare. To fully address the needs of all households experiencing housing instability and homelessness in Philadelphia, the plan proposes “programs and policies that will support new housing opportunities for 36,500 households and preservation of 63,500 currently occupied homes in 10 years.” The total 1o-year price tag is about $6.2 billion (across federal, state, local and private sector resources).

This community was identified in last week’s blog post as a peer community for Charlotte-Mecklenburg.

CAN BE OWNED BY EVERY STAKEHOLDER

A plan is ultimately only as good as its implementation. The extent to which any plan can be operationalized with fidelity is a key measure of the success of the planning process. Operationalization depends upon multiple factors. Is the plan easy to understand? Does the plan clearly outline the steps necessary to achieve the goals and objectives? Can everyone and/or every group find a space within the plan to be involved? Will everyone and/or every group take responsibility for implementation of the plan? Is this true, even if sacrifices are requested of an individual or entity? Is there truly shared ownership of the plan?

Shared ownership is as much a reflection of the process to develop the plan as it is the content within the plan, itself. Ownership starts at the beginning and continues throughout the life cycle, from the earliest phases of development to long after a plan is released. This means that the process of plan creation must involve as many voices as possible, from all levels of stakeholders and in all sectors of the work. And, not just from within the housing sector. The process must ensure that all perspectives are represented, which may require proactively recruiting individuals and/or groups with different and/or opposing viewpoints to be part of the work to identify solutions. If the process is done well, implementation of the plan will actually begin while it is being crafted, and simply continue after it is fully developed and released.

Highlighted below is one example of a housing strategic plan which had an inclusive development process:

Austin Strategic Housing Blueprint

Adopted in 2017 by the Austin City Council, the goal of the Austin Strategic Housing Blueprint is to create 135,000 affordable housing units by 2028. At the time the plan was released Austin faced a shortage of 48,000 units for extremely low-income households (below 30% of AMI).

Community engagement was considered a key component of the process. This included multiple levels of stakeholders from different backgrounds through a variety of means and methods, and even languages.

Included below is the excerpt from the plan that summarizes the steps taken regarding community engagement:

“Community Development Department (NHCD) staff actively solicited input from residents, community leaders, local housing advocates, and board and commission members for this Blueprint. Citizens had multiple opportunities to provide input through a variety of methods. NHCD staff hosted 13 Community Conversation meetings, with at least one in each council district, as well as additional stakeholder meetings and presentations at multiple board and commission meetings in spring 2016. This outreach provided an opportunity for more than 400 stakeholders to discuss the difficult choices the city faces regarding household affordability. In these dialogues, citizens were asked to discuss various funding mechanisms, potential regulations, and other creative approaches the City could utilize to increase housing choices for a range of incomes. The activity was designed to foster constructive communication between community members about issues relating to affordability. Input gathered from this process informed the Blueprint Additionally, a Housing Conversation Kit was created so that individuals could host their own conversation with their neighborhood association, civic group, non-profit, or faith-based organizations to discuss their perspectives on housing. […] A draft of this Blueprint was presented to the Housing and Community Development Council Committee on June 6, 2016, followed by further stakeholder engagement during the summer and fall of 2016. Requests for public feedback on the draft Blueprint were emailed to all stakeholders involved in the spring engagement process as well as non-profit, housing advocacy, and neighborhood group networks. Stakeholders had the opportunity to email their comments and suggestions on the draft Blueprint directly to NHCD, contribute to the discussion of the Blueprint on the SpeakUP! Austin online platform, and provide comments at all 22 public library locations, where physical copies of the draft Blueprint were available for public review. Outreach was advertised through the City of Austin social media platforms, CityView community access telvision, and Span-ish-language media.Two additional community-wide meetings were held as well as eight targeted meetings for low-income and minority communities in Council Districts 1, 2, and 3. A total of 119 individuals attended the meetings and 18 formal comment letters were submitted from individuals and organizations. [A] Feedback Log Includes staff responses to more than 400 stakeholder comments on the draft Blueprint.”

This community was identified in last week’s blog post as a peer community for Charlotte-Mecklenburg.

SO, WHAT

A good housing strategic plan will include the components highlighted above. But, checking off these boxes, while good, will not be enough. Any good housing strategic plan must be achievable. If the plan includes elements that will never be possible in a given local context, then it becomes merely an aspirational exercise that will not lead to meaningful change.

To be achievable, a good plan need not reinvent the wheel. Wheels have been around for a long time. They get the job done. As communities work to develop strategic housing plans, they can pull “what works” from existing resources (both from the within their own community, and from the outside, by adapting strategies from other communities with similar local conditions). Innovation can be a simple aggregation of existing strategies, if the aggregation results in a product that is comprehensible, coherent, and feasible.

At the end of the day, a good plan is measured by the outcome produced. Think about the blueprints for a house. There is a lot of work that goes into the blueprint. Beyond design, there are standards that must be met, math that must make sense, physics that must be respected. The blueprint has to ensure that the structure it creates will stand.

But it is the house, not the plan, that is the true reflection of a good blueprint. It is the house itself that is the outcome, not the architect’s drawing. Similarly, the true measure of success for a community’s strategic housing plan will be if there is enough housing that is affordable and available for every single person who needs it in the community.

SIGN UP FOR BUILDING BRIDGES BLOG

Courtney LaCaria coordinates posts on the Building Bridges Blog. Courtney is the Housing & Homelessness Research Coordinator for Mecklenburg County Community Support Services. Courtney’s job is to connect data on housing instability, homelessness and affordable housing with stakeholders in the community so that they can use it to drive policy-making, funding allocation and programmatic change.