Courtney LaCaria

Housing & Homelessness Research Coordinator

Mecklenburg County Community Support Services

Last month, the Building Bridges blog launched a new series devoted to unpacking some of the most commonly misunderstood housing and homelessness terms and concepts. The first post in the series was dedicated to exploring and exploding some misperceptions around “Housing First;” the second post unpacked Naturally Occurring Affordable Housing (or NOAH); last week’s post covered the role of supportive services in the work to end and prevent homelessness. These posts are inspired by the 2025 Charlotte-Mecklenburg Housing & Homelessness Strategy (CMHHS), which was launched in April 2021.

The 2025 CMHHS represents the first time that the public and private sectors have come together to comprehensively address the entire housing continuum, from housing instability to homelessness, in Charlotte-Mecklenburg. Over 250 individuals and 115 organizations have signed up to participate in the planning and development process. This includes the work currently underway to outline draft recommendations from each of the nine workstreams.

Four of the workstreams, which are devoted to the main impact areas of the strategic plan (prevention; temporary housing; permanent, affordable housing; and cross-sector supports), will be sharing information through focus groups in July and August. Anyone is welcome to sign up via this link to learn more and share feedback; please share this opportunity broadly.

As the last post in this series highlighted, advancing widescale solutions – even the ones backed by research and data – also means overcoming obstacles that have historically gotten in the way. Some obstacles take the shape of myths or misconceptions.

This week’s post focuses on the first of five common myths and misperceptions about affordable housing, and ultimately, what correcting these misunderstandings can mean for the work to end and prevent homelessness in Charlotte-Mecklenburg.

WHAT IS AFFORDABLE HOUSING?

Housing is generally considered “affordable” if a household does not have to spend more than 30% of their pre-tax, gross annual income on housing-related expenses. Those that pay more than 30% of their gross income on their housing-related expenses are identified as “housing cost-burdened.” “Housing-related expenses” includes not only the cost of the rent (or mortgage), but utilities and all other expenses directly related to sustaining their housing.

The term “affordable” is generally applied to households ranging from 0% to 120% of a geographically associated Area Median Income (AMI). Using FY2021 data for a family of four in the Charlotte Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA), this annual income range spans from $0 all the way to $101,040. The Fair Market Rent for a 2-bedroom apartment in Mecklenburg County is $1,151; this number does not include utilities and other housing-related expenses. A four-person household at 30% of AMI can afford (at most) $663 per month in rent and utilities without being cost-burdened. In contrast, the same size household at 80% of AMI can afford $1,684 per month in rent and utilities.

Permanent, “affordable housing” more typically is used to refer to the physical units, themselves. But the term can also encompass financial assistance provided to gap the difference between what housing costs and what a given household can afford. Examples of financial assistance include short-term rental subsidies, such as rapid re-housing; as well as long-term subsidies and/or vouchers, like permanent supportive housing and Housing Choice Vouchers. Financial assistance is funded by both public and private entities at the local, state, and federal levels.

Therefore, there are three primary considerations related to permanent, affordable housing stock: preserving existing units and resources; adding new units and resources; and removing barriers to available units and resources. Preserving existing housing inventory includes the retention of Naturally Occurring Affordable Housing (NOAH) and other lower-cost rental units, as well as the rental subsidies needed to gap the difference in cost and affordability.

DOES “AFFORDABLE HOUSING” MEAN….?

There are multiple myths and misconceptions regarding affordable housing. Many have been around for a long time and are revived whenever there is a new development or policy proposed. It is important to note that these myths are not limited to Charlotte-Mecklenburg.

While this is not meant to be an exhaustive list, outlined below are five of the top affordable housing myths; this blog post will focus on the first of the five, unpacking the myth, itself, and highlighting examples from other communities that have attempted to reframe and reclaim the truth:

TOP 5 AFFORDABLE HOUSING MYTHS

- MYTH 1: DOES AFFORDABLE HOUSING MEAN….LOSS OF NEIGHBORHOOD CHARACTER?

- MYTH 2: DOES AFFORDABLE HOUSING MEAN….UGLY BUILDINGS?

- MYTH 3: DOES AFFORDABLE HOUSING MEAN….LOW QUALITY?

- MYTH 4: DOES AFFORDABLE HOUSING MEAN….HIGHER CRIME RATES?

- MYTH 5: DOES AFFORDABLE HOUSING MEAN….LOWER PROPERTY VALUES?

MYTH 1: DOES AFFORDABLE HOUSING MEAN….LOSS OF NEIGHBORHOOD CHARACTER?

A local article covering a 13-hour comprehensive plan hearing in Washington, D.C. summarized the arguments for and against around the following question, “What’s more important: creating needed housing or protecting neighborhood character?” This debate cuts to the heart of one affordable housing myth. This myth, which is typically associated with the concept of residential intensity, assumes that affordable housing and neighborhood character are mutually exclusive. To address the myth, we can separate these components for further analysis. First, let’s tackle the concept of residential intensity.

Intensity is not a monolith; rather, there is a spectrum of different typologies, ranging from single-family, to duplexes; townhouses; mid-rise apartment buildings; and large apartment complexes, to name a few. Density and intensity are governed by a municipality’s zoning ordinances.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg, the City of Charlotte and each of the six towns have their own, unique zoning ordinances. For example, using the City of Charlotte’s current development ordinances, single-family zoning includes R-3, R-4, R-5, R-6, and R-8. R-3 and R-4 districts (which means that no more than 3 or 4 housing units per acre) are “directed toward suburban single family,” whereas R-5, R-6, and R-8 districts (which mean no more than 5, 6, or 8 units per acre) “address urban single-family living.” Multi-family districts include R-8MF, R-12MF, R-17MF, R-22MF, and R-43MF, which range from as few as 8 dwelling units per acre to as many as 43 dwelling units per acre. Examples from the Town zoning ordinances use different district terminology, including “general residential” (which includes low-density single-family zoning); “low-intensity residential” district; “medium density residential” district; “neighborhood residential”; and “neighborhood mixed use,” which includes medium densities and multi-family use. Even within the boundaries of Mecklenburg County, zoning and development ordinances and practices are not “one-size-fits-all.”

The second part of the myth deals with “neighborhood character,” which can mean multiple things. Different parts of a municipality can and do receive different designations, to generally incentivize a community to use land according to a larger plan or vision. Some municipalities intentionally minimize industrial or intense residential development opportunities, often in service of preserving the “character” of a neighborhood, or even an entire township.

A recent article by Slate.com provides a helpful depiction of this construct’s metamorphosis vis-à-vis housing planning and development in Los Angeles. As context, the Los Angeles metro area has only 20 affordable and available rental homes per 100 renter households (the third worst shortage of all major metro areas across the country, using data from the 2021 Gap Report by the National Low Income Housing Coalition). The Slate.com article points out the historical barriers that have limited housing growth, such as the attempts to control population growth and banning low-rise, multifamily housing during the 1970s and 1980s. Despite changes, housing growth per capita in Los Angeles continues to be relatively low.

According to a 2019 analysis by CityLab, Los Angeles ranks third from the bottom in a list of major U.S. metros with fewer than 4 housing permits per 1,000 residents between 2008 and 2018. In comparison, the city of Charlotte issued 7 housing permits per 1,000 residents during the same period. While higher than other metro areas, the rate in Charlotte represents a significant decrease from more than 12 housing permits per 1,000 residents between 1990 and 2007; further, most of these 7 permits per thousand were for single-family homes.

Trying to meet the demand for housing at all price points with diminishing options for developable land, Los Angeles, like many communities in the United States, has explored opportunities to increase intensity (and thereby, maximize available resources), only to be stymied by narratives like “neighborhoods are changing too fast” or “loss of neighborhood character.”

So, the city of Los Angeles launched a design challenge called: Low-Rise: Housing Ideas for Los Angeles. The goal of the challenge was focused on changing hearts and minds by starting a different kind of conversation.

Below is an excerpt, summarizing this goal and how the challenge attempts to achieve it:

While residents of L.A.’s wealthiest single-family neighborhoods make up a powerful political force that, when mobilized, can forestall changes to zoning in low-rise neighborhoods, there is also widespread concern among homeowners and renters in communities of color about the prospect of new development, even of relatively modest density, and the broader forces of displacement, gentrification, and disruptive change that development can sometimes unleash. With nearly a third of the city’s single-family homes occupied by renters of color, these fears are anything but abstract. We won’t build support for more housing options in single-family neighborhoods and other low-rise areas of the city until we can address the concerns of existing communities and, at the same time, really grasp the range of benefits that change will bring: for future residents as well as current ones, for renters and homeowners alike.

Here’s where architecture and landscape architecture come in. Any significant shift in the way we build housing in Los Angeles will be doomed to fail unless it produces an appealing vision for a new kind of living. Unlike the acceleration of single-family construction after World War II, which got a major boost from the popularity and charisma of the Case Study houses and other models of stylish postwar living, the campaign for low-rise infill housing has so far lacked a strong architectural component in Los Angeles. The resulting vacuum — not just of architectural imagery but also of architectural expertise and intelligence — has left room for doubt, anxiety, and even misinformation about changes to housing policy to take root.

As a result, much housing coverage has focused on the polarization visible in differences of opinion between opponents of denser housing development (so-called NIMBYs, for their Not in My Back Yard attitude) and advocates of more aggressive housing production (so-called YIMBYs, for Yes in My Back Yard). The coverage tends to ignore the huge numbers of citizens who fall somewhere between these extremes: open to zoning changes as they consider histories of exclusion and the specter of climate change but wary about what broader forces—from displacement to gentrification to speculative investment from outside entities—those changes might bring forth in their own communities and on their own blocks. […]

We aim to fill this long-standing vacuum with a measured, thoughtful, and productive series of architectural ideas. Architects and landscape architects, after all, possess an particular set of skills that we believe will be hugely helpful in clarifying a path forward for our low-rise housing policy and illuminating the ways in which certain changes to that policy, in bringing new flexibility to our low-rise housing stock, will be worth looking forward to. […]

Low-Rise: Housing Ideas for Los Angeles is a design challenge meant as a significant first step toward that conversation […]We began our work on this design challenge by engaging community experts in housing and asking them, in a series of listening sessions organized by theme, how they and their fellow residents would like to see their neighborhoods evolve. Their answers to that question and others have directly shaped this brief. […] The result is that communities are explaining to the participating architects what they’d like to see in their neighborhoods and asking for their help in turning those ideas into a series of design proposals.

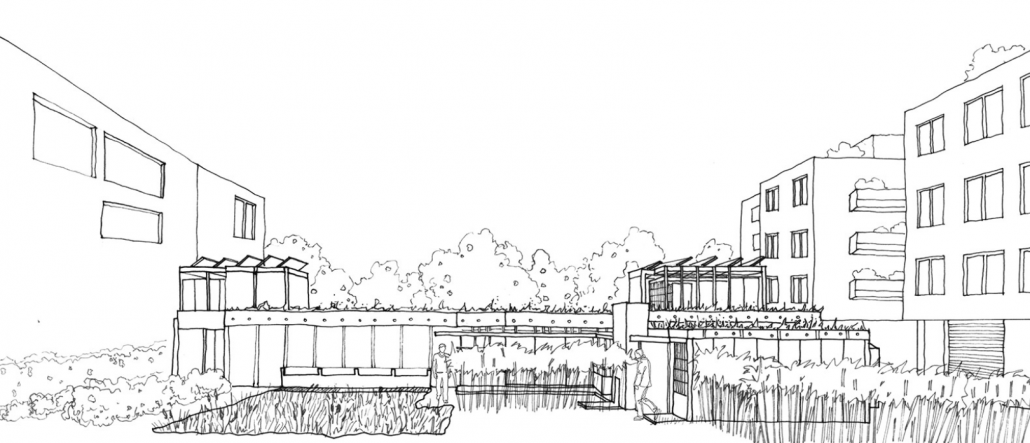

The result? The winning selections among four categories depicted below (redistribution, subdivision, fourplex, and corners) demonstrate that multi-family housing can look like housing within single-family zoned districts. However, all of the winning designs also require changes to local laws, such as relaxed parking requirements; smaller lot sizes; and mixed-use zoning.

The hope remains that steps like these can help all levels of stakeholders in the community break down the barriers that are contained in the myth and misperception; literally see what could be possible; and ensure that such changes could be welcomed by neighborhoods. To that end, the winning designs selected will inform “a process of reengagement with L.A.’s low-rise neighborhoods, one that will be well timed to inform the ongoing updates led by the Department of City Planning of specific Community Plans and the city’s overarching Housing Element. They will be part of a larger process to reimagine what it means to live the good life in Southern California — and to understand the ways in which the good life, to be good for everyone, must also be sustainable and equitable.”

SO, WHAT

Both locally and across the United States, there are not enough units at all price points to meet the overall need for housing. This situation puts additional pressure on households with the lowest annual incomes. Currently, Charlotte-Mecklenburg has a gap of 23,060 affordable rental units just for households with incomes at or below 30% of Area Median Income.

To close the housing gap requires that communities increase the supply, which typically means increased density and intensity. Considering that the affordable housing gap is expanding; land is only getting more expensive; and the open space to develop low-intensity housing is decreasing, this difference in density is significant. So, where does new affordable housing go?

The architect of the “Low-Rise: Housing Ideas for Los Angeles” states, “Our design challenge is meant to address that very question: to provide some ideas about what that housing might look like, how it might fit comfortably and attractively into existing neighborhoods, and what it might be like to live there.”

Seeing can be, if not believing, at least the first step in understanding. There also must be a willingness to reach understanding, regardless of how concrete a concept may be…or how ingrained a misperception has become. Understanding that every member of our community has intrinsic worth, and is deserving of housing solely on the basis of our shared humanity, is necessary to combating all housing myths. Communities, like Charlotte-Mecklenburg, must find ways to provide that housing, while addressing the concerns around increased intensity and changing neighborhood character.

Stay tuned for future posts covering common housing and homelessness-related misconceptions and myths. And, please consider signing up for one of the upcoming CMHHS Focus Groups in July and August to learn more information and provide feedback. To register, click this link.

SIGN UP FOR BUILDING BRIDGES BLOG

Courtney LaCaria coordinates posts on the Building Bridges Blog. Courtney is the Housing & Homelessness Research Coordinator for Mecklenburg County Community Support Services. Courtney’s job is to connect data on housing instability, homelessness and affordable housing with stakeholders in the community so that they can use it to drive policy-making, funding allocation and programmatic change.